“We all live in a house on fire, no fire department to call;

no way out, just the upstairs window to look out of

while the fire burns the house down with us trapped, locked in it.”

— Tennessee Williams

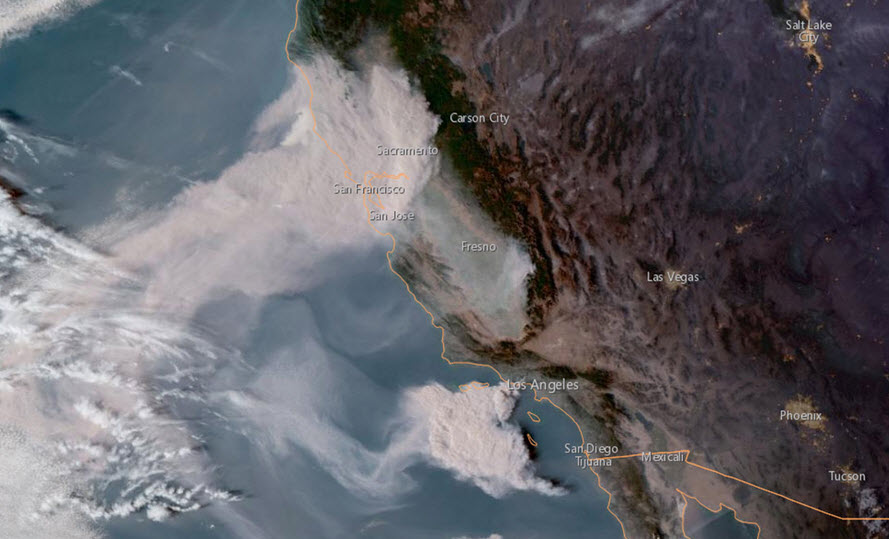

From 2016 to 2021, the fire season seemed to grow worse and worse every year in California. Extended, below-average rainfall killed hundreds of millions of trees. By 2020-21 it was so intensely hot and dry, and the availability of fuel so abundant, that the entire state was a powder keg of stored-up energy on the verge of spontaneous combustion. Eight of the state’s top ten fires in its history occurred during this period. Millions of acres were torched, entire towns were destroyed, and megatons of carbon entered an atmosphere that was already at its highest levels in eons.

What is fire, anyway?

Science tells us it is the rapid oxidation of a material, and that the flames are nothing more than gases and water. The chemical reaction of conflagration releases energy that makes it hot. Anyone who has ever sat next to a mountain lake and stared into a dancing campfire will tell you there’s something else there… something much more than a chemical reaction. The flickering flames are but physical manifestations of a boundless, insatiable consumption that has character, and a life of its own. It may not be the biological sort of life about which we are taught in school, but it has all the qualities of life: energy, animation, feeding activity, propagation, and an obsession with staying alive. Science tells us that if there was a higher percentage of oxygen in the atmosphere, all matter would spontaneously burst into flames. This oxygen that we breathe, and without which we would quickly perish, is a catalytic converter of the highest order in the material universe. Fire is its agent.

When the combustion of oxygen gets too hot, it can form plasma: the energy of physical creation, and fuel of stars. Countless billions of stars are burning plasma in nuclear fusion, all at the same time; throughout the entire known universe, projecting their solar radiation outward into mostly empty space. Our own Sol releases about 380 septillion joules of energy every second. It has been said that the sun releases more energy in that one second, than all humankind has used in its entire history. Back on Earth, the plants capture this bounty as tiny packets of energy, and convert them into carbohydrates, releasing the oxygen into the atmosphere so it can burn again.

The sun bombards our planet with solar energy, and only a fraction is converted to oxygen by photosynthesis. But even that represents an incredible amount of energy, which eventually accumulates in plant matter as carbon. This also pulls harmful carbons from the atmosphere, preventing a greenhouse effect across the globe. All that is now reversing in the relative blink of an eye; with the wildfires burning across the globe – especially in Siberia, and western North America. Megatons of solar energy are being transferred to the atmosphere, via an unstoppable, natural chemical reaction. This can only accelerate the effects of global warming and climate change, at a time when human civilization must do everything it can to reduce its carbon emissions in order to survive. No Kemosabe, this doesn’t look good at all.

One of the greatest traditions when camping is to build a controlled fire in a ring of stones. It is an ancient and symbolic ritual; an assertion of our tenuous control over a natural force that could easily destroy us. We surround the blaze with a wall of rocks, and domesticate it for our puny utility. Sometimes the beast escapes and ravages its surroundings; even its handlers. Most often, it pops and hisses jealously within its enclosure; ever alert for escape, as its endless appetite is fed by human hands. But left unchecked, it will seek to destroy every gram of matter on the planet. When man (or woman!) discovered fire, she discovered life… and death, too.

Plato spoke of the shadows we cast when fire illuminates the cave of our minds. He claimed the shadows were our delusions, and not the true reality. The ancients worshiped fire, and used it for religious purposes. Since that long-ago cave, modern engineers have harnessed the power of combustion for millions of purposes, from the tiny spark in a motor to the hydrogen bombs that could destroy all life as we know it. It seems Plato was on to something.

Think of those cave people, huddled around a campfire in ancient times, absorbed in its power to provide warmth and stave off the demons of the night… Everyone agrees that the discovery of fire was one of the singular events in human history. More to the point: it was learning to “control” fire, and use it towards our own ends, that elevated us from a frightened, vulnerable species to the masters of all life on earth. By masters I don’t mean to imply we have it all figured out – rather, that we treat all “lower forms of life” with contempt and indifference, as if they exist only to serve our needs. Fire gave us humans the ability to control our environment, and we responded by metaphorically leaving all our campfires unattended until they are literally destroying us. If Smokey the Bear was in charge of human development, he would have stomped us out a long time ago.

“Someday, after mastering the winds, the waves, the tides and gravity, we shall harness for God the energies of love, and then, for a second time in the history of the world, man will have discovered fire.”

― Pierre Teilhard de Chardin

Only You Can Prevent Forest Fires

The majority of California’s fires are started by lightning, in rugged locations that attract weather and hinder direct access for Cal Fire crews. Years of drought, underfunding, and mismanagement have provided an excess of dry, pitchy fuel throughout BLM and National Forest lands. When the mega-fires came, firefighters could do little more than direct the flames away from structures, and even that wasn’t always successful. At one point, over 200 fires were burning from one end of the state to the other. It was only a matter of time and chance before the luck of my beloved Bear Lakes Basin would run out. By August 2021, a monstrous conflagration called the “Haypress” fire developed in the upper Coffee Creek watershed, and slowly crept north towards the very spot where the Epps Men camped earlier that summer. It had already burned over 60,000 acres by the time I noticed the reports, and was only 8 miles away as the crow flies – except that a crow would be smart enough to head away from it! I began to worry that my favorite place on Earth was about to be burned to a crisp.

— By Sept 1, the Haypress fire was only about 5 miles away, still spreading along a northerly path headed straight for the Bear Lakes Basin, and spewing hot spots up to half a mile ahead of its leading edge. Elsewhere, in the Sierras, the “Caldor” fire forced the evacuation of the largest city in the mountains of California: South Lake Tahoe. Ski resorts deployed their snow-making machines as giant fire hoses in an attempt to turn away the flames. Still no rain in sight…

— I watched helpless on my computer screen as, day after day, the massive Haypress fire crept closer and closer to my spiritual home. Google Maps rendered the development of the catastrophe in astonishing accuracy and drama, with thermal-sensing satellites identifying the hot spots through the thick smoke. I was old and disabled, and in no condition to fight forest fires in rugged terrain, but in my imagination, I lined up a dozen snow-making machines at the top of the rim, with hoses leading down to the lake. I wanted to be there so badly, to help save my paradise from destruction. I thought of the dry tinder box that was Lothlórien, and of the many trees I knew and admired…

— A week later, the leading edge of the fire was less than 3 miles from the southern rim of Little Bear Lake, and the thermal hot spots were approaching Eagle Creek, which was under mandatory evacuation. The Haypress fire had merged with another fire to the south, and was now more than 130,000 acres in size, with 0% containment. Humidity continued to be extremely low, giving the fire free reign over the hot, dry terrain. Cal Fire had focused all its energy and resources on saving South Lake Tahoe from the Caldor fire; and now, with so few structures and human habitation, the fires in the Trinity Alps were simply a low priority.

I have had many disappointments in my life, and have developed a coping strategy where I prepare for the worst, and hope for the best. Mentally, I began to consider what would happen if the fire crossed Eagle Creek just to the south of Little Bear Lake, and roared up the mountain slope to engulf the basin. The advance embers would be blown over the rim by a fierce, hot wind, alight in the tinderbox of Lothlórien, and ravage every tree I knew and loved. Perhaps some of the outlying trees would be spared, but the lake basin would be incinerated.

A self-preserving sort of rationalization took hold in my head, wondering if perhaps this could be a good thing. After all, mountain ecosystems have adapted to fire, and over the long run, a disastrous conflagration could be beneficial for the soil and plants, and eventually the animals would return. Unfortunately, that would take decades to happen – after I, too, had returned my carbon molecules to the planet’s “bio-library.” I would never witness the Bear Lakes in their former glory again. I looked through the hundreds of pictures I had taken over nearly 50 years of visiting the area, and imagined what the spectacular views would look like with only charred, black skeletons remaining.

— By September 9, thunderstorms and “dry lightning” were starting new fires all over Northern California. With such low humidity, the scant rain from those storms usually evaporated before it hit the ground. This time, however, the moisture had a dampening effect on the fires, especially at higher altitudes. It subdued the hot spots, and gave the firefighters a chance to get in there and knock it down even more. If I was standing on the Observatory rocks today (and could see through the smoke), I would see the approaching flames just 2 miles away to the southwest; 3,000 feet down on the other side of Eagle Creek. It wasn’t over yet.

— I discovered daily video briefings of the fire map, sponsored by the U.S. Forest Service. The main focus was, of course, on inhabited areas such as Callahan to the north, and Trinity Center to the southeast. The fire captain mentioned that men and equipment would be extending access throughout the Eagle Creek Loop, which was good news for the Bear Lakes Basin. There were far fewer hot spots now, which meant the fire wasn’t spreading as rapidly as it had the week before. The forecast was for hotter temperatures, however, which could be a problem.

— September 15 came, and the fire had stalled. The smoke cleared up a little, allowing aircraft to dump flame retardant on the ridge between Stoddard Lake and Eagle Creek, less than 10,000 feet to the south of my vulnerable paradise. There were still several active blazes because of the clearing air, and the winds were predicted to increase before the promise of a cold, moist front from the north might be fulfilled in a few days. Hot spots jumped down from Callahan and invaded the Tangle Blue Lake valley just to the northwest of Big Bear; if only to prove they could fly through the air unexpectedly, and take hold in a completely new area. The Bear Lake Basin was now threatened on two sides.

While all this was happening in the Trinity Alps, a new fire had developed in Sequoia National Park; in extremely rugged terrain that prevented firefighters from making a stand to save the giant trees. The General Sherman Tree – the largest living tree on the planet by volume – was wrapped in large sheets of aluminum foil to protect it if the flames invaded the focal grove of the park. This location was too far south to gain any reprieve from the slow-moving cold front sweeping down from Alaska, but hopefully it would push some humidity into the region. Until then, voracious flames licked at the toes of the largest living things in California. The Cal Fire website still showed more than 30 active blazes across the state.

With firefighters heroically pulling double shifts, but unable to do more than harass the edges of the fire, it became a race to see if the weather would arrive in time to save the trees of the Bear Lakes Basin from destruction. They had already tried, and failed, to save the beautiful Stoddard Lake area from being ravaged, just before the fire reached Eagle Creek. But this new location gave them significant access to the heart of the inferno, and they focused all their heavy equipment in the area to try and prevent it from spreading north to Callahan – right through my favorite vacation wonderland! I prayed to all the gods for water to fall from the sky, and deliver us from the ruin we had wrought upon the forests.

— A few days later, the first “atmospheric river” event of the year arrived on the Pacific Coast, dumping 3-6” of rain in Washington and Oregon. By the time it reached California it had been nearly sucked dry, but it still had enough moisture to shroud the Haypress fire in a humid blanket of less than an inch of rain. This nearly miraculous event was exceptionally early for the season, and so many prayers were answered. The fire diminished significantly, and crews were able to make gains in containing the conflagration. Aircraft focused on the Tangle Blue Lake area, reducing that threat to nearly nothing. Hotter, drier days still lay ahead, and the fires could rejuvenate quickly with so much fuel available, but it looked as if the worst was over.

— By September 25, the entire fire’s perimeter had largely been unchanged for a week. It was nearly 200,000 acres, but weakening rapidly. That early cold front dulled its vigor, and now another one was rolling down from the northwest; bringing higher humidity and cooler temperatures. There were already scattered showers at the higher elevations in the Trinity Alps, and the Haypress demon was doomed. The established fire lines held fast, the scorched land cooled down, and only deep embers remained. In just a few days, the whole abomination was almost 80% contained. The Bear Lakes Basin and all my forest friends were safe!

How did all that happen?

The burning of California in the 21st Century is surely one of the most catastrophic, widespread natural tragedies in recent geological time, and it’s not over yet! The planet has endured many droughts in its history – a fact to which the deserts of five continents will attest. But this is the first mass arboricide event that has 8 billion human witnesses; nearly all of whom are in some way responsible for it.

On top of everything else, this causes an overwhelming depression and anxiety in the population, as if we are all doomed and defeated. This goes by many names, but I relate to the term “ecological grief.” I feel it myself, as my soul cries out in anguish over the slow destruction of our ecosystem, and especially the threat to my beloved Bear Lakes Basin. This despair and hopelessness breeds apathy instead of activism, and causes us to become more isolated and selfish, at a time when we all absolutely must work together for the common good. Hell, we can’t even agree about wearing masks during an airborne global pandemic – do you really think a politically significant number of people are going to demand action from world governments on climate change? Instead, the ignorant masses will congregate for anti-vaccination protests; vehemently defending their inalienable right to die by natural selection.

What really gets to me is when people act as if climate change and intensifying natural disasters shouldn’t be happening. On the media and in office conversations, folks complain about the weather, the worsening storms, and the loss of forests and clean air. They wring their complicit hands and lament the drought and higher temperatures. But OF COURSE this was going to happen – scientists had been warning us about it for at least 50 years! And yet, we willfully ignored their pleadings and continued our lust for consumption unabated. In fact, the manic consumerism, avaricious extraction of resources, wanton ecological destruction, and careless emission of carbon into the atmosphere have increased sharply during that same period. If you had a teenager who refused to clean his room when you told him to; then started complaining about the smell after years of unheeded counsel, would you feel sorry for him?

I feel we are part of an extinction event of our own making, and we are past due to come to grips with that fact. It’s time to get our mental and spiritual affairs in order, for the physical concerns are a lost cause. It seems human beings are just a clumsy misstep in a much greater journey of life on this planet, which we call “evolution.” Our species is a relative newcomer to this experiment, and it was going rather well until we fucked it all up. It seems the only niche we occupy in the ecosystem is that of a malicious parasite that wants to kill our host. In a scientific sense, we are the adverse event in this research study – the anomaly, if you will – but the experiment will continue without us. As we give but little for the greater good of the whole, we won’t be missed.

“If it were not frightening it would be amusing to observe the pride and complacency

with which we, like children, take apart the watch, pull out the spring and make a toy of it,

and then are surprised that the watch stops working.”

— Leo Tolstoy