the happiness of complete isolation. Something which seems outside life.

Something therefore like the longing for eternal peace.”

I don’t remember getting back in my tent, but I awaken in the early dawn with all my clothes on, lying stiffly on top of my sleeping bag like a fallen log. I am so tired, but my first act is a smile of gratitude for all that I had so richly experienced the night before. The corners of my mouth curl with a wry twist of irony when I remember that today is Independence Day: the day on which I must return to my dependent lifestyle.

Zing! I unzip the tent before sunrise, and it pierces the stillness; clear as a bell, signaling the arrival of breakfast… but there are no mosquitoes at all! This gives me a few extra hours in paradise. I have a sudden notion to go back out to The Altar and watch the sun rise, as God’s Church rotates around again to face our home star. I tug on my boots after shaking them out carefully, remembering the snake from the night before. I do this out of habit, even when my boots are inside the tent. Remembering to pamper my legs, I grab my staff and pick my way eagerly back to the sanctuary.

I arrive just in time. All the clouds from last night are gone, and the sky is clear and bright. The sun peeks over Mt. Shasta to the east, at the very moment I lay my walking stick against The Altar. How remarkable that on the Summer Solstice, from this sanctuary, the sun can be observed to rise from directly behind the Holy Mountain! The solstice was 14 days ago, and the sun is already moving south. The point where it rises today is just a degree or two south of the very peak of the ancient volcano that dominates this region in so many ways. This is surely a highly significant spot!

Dumbstruck by yet another phenomenon, I turn all around to see the full effects of the sun’s first exposure of the new day. Sawtooth is dramatically lit from the side, in high relief. The tall pines near its base are stretching out shadows that must be over 200 yards long. Diffused amber beams of dawn-kissed light are flowing up the valley. Behind me, the pinnacles of Altamira are infused with their usual alpenglow as The Sentinel greets a new day. At my feet, Wee Bear is dark and ruffled, its surface still deep in shadow, but the wall behind is lit up like a canvas in an art gallery. Sphinx Rock and Cheops are also in the shadows, with the sun rising over their shoulders. I turn full circle back to the east to face the sacred body of Queen Shasta, with a blazing star hovering above her crown. The mornings are very different at all 3 lakes, but each is spectacular in its own way. Big Bear has the largest mirrored surface, reflecting the entire basin of rim rock. Little Bear has the Great Wall behind it, with the sentient stillness and emerald green waters of the cove. Wee Bear may be the most amazing of all, with its panorama of splendor and multiple viewpoints.

There have been so many fantastic revelations in the past 24 hours of this trip. As many times as I have been up here, I thought I had experienced all the best that it had to offer. Instead, layers upon layers are opening to me like a lotus flower, revealing the innermost soul of the place. It still has one more surprise for me.

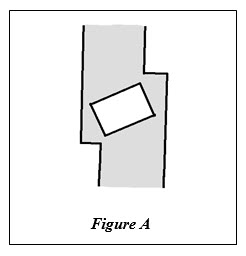

Looking down at where I’m standing, right next to the central altarpiece, my eye is caught by an odd feature of the granite I hadn’t noticed before… not in 11 previous trips to this spot. I’m standing on a gunmetal green band of darker rock about 18 inches wide. Throughout this small basin where Wee Bear lies, there are many such veins of different granite – from sage to dark gray – running more or less vertically through the knoll. My eye traces this one from the back wall about 50 yards behind me, passing under my feet through the heart of the sanctuary, and down towards the Beater Cedar an equal distance below, where it disappears over a ledge. As if altered by the energy of this spot, the entire band shifts 6 inches right where I’m standing, forming a rough square (see Figure A).

The incredible anomaly I noticed lies within this dark square: a perfectly shaped rectangle of white granite that is tilted at about a 45 degree angle to the sides of the dark band of granite. Incredulous, I get down on my knees to examine the joint between dark and light granite, but there is no joint. It is seamless, as if it had been inlaid by a master mason. There are definitely two different types of granite in this square – the color, texture and grain are quite disparate. I can think of no logical or geological explanation for this phenomenon, and can only defer to my first spontaneous, emotive reaction: “Oh, my God!”

I wish Dave were here to offer some scientific insight, but the theory of how this rock formation could have been rendered is beyond my ken. It must have been a very special process, considering this spot and its relation to the summer solstice and Mt. Shasta. My over-boggled mind reaches an unprecedented level of bogglement. When I got home, I pored through books and Internet sites on pyramidology and sacred geometry, but could find no reference to such an arrangement of a rectangle inside a square. Then I stumbled across a trigonometry problem of how to calculate the largest rectangle that would fit perfectly inside a square, with all four corners touching the sides of the square. This seems to be what the image was trying to represent; in almost mathematical precision. When you take into account the massive forces that forged this area, and the effects of living magnetism and sacred geometry on the planet as a whole, the assumption that this is a random formation becomes obstinate vanity.

Following this line of research, I could not get this curious rock formation out of my mind. I searched several geological sites on the Internet to try and discover how it came to be frozen – in a manner of speaking – inside solid granite. This entire mountain range is volcanic, forged from igneous rock in the crucible of magmatic activity, and crystallized out of the random surging and mixing of molten lava. Somehow, this block of lighter granite was trapped in what geologists call a “dike,” when the cooling igneous rock split into giant sections, forming a crack with straight edges into which an upwelling of hotter, darker granite surged forth like blood from a cut. Then it all cooled to form this mountainside, fixing the lighter block with its cuboid shape inside the darker vein of granite. As eons passed and the earth entered its Ice Age, a glacier wore down the knob of exposed granite over several millennia, scraping away layers of rock until it exposed the symmetrical design. Then this large, flat boulder I call The Altar was left right next to it as the ice melted away. I have never seen anything like this cuboid formation in the dike, either in person or in my modest research. It would be an interesting geological curiosity anywhere in the world, but what science cannot tell us is: why did it happen right here, next to a stone shaped like an altar, from which the sun can be seen to rise directly over Mt. Shasta on the summer solstice?

Only the truly humble can admit that there are forces and laws of nature far greater than our ability to perceive them. The more one knows, the more one learns how much one doesn’t know.

The sun is advancing higher in the morning sky, and sadly, I must break away from this remarkable discovery to attend to domestic trifles. After breakfast, I fiddle with that darn phone charger contraption again, to see if it might decide to work today. I so very much want to get some more photos! Amazingly, it powers up the very first time I push the same button that I tried several times yesterday. Duh!! Now it’s charging my phone happily: a bit of artificial technology fulfilling its purpose. Isn’t that delightfully trivial? I will take lots of photos the rest of the morning, and gather a few memories to hold me over until the next time – God willing. Maybe I’ll leave after lunch when the sun is high in the sky. Normally, it’s the worst time of day to cross the bare granite back to the trail, but there are currently high clouds blocking the sun, which makes the temperature nice and pleasant. I have plenty of daylight to work with, and could be home by midnight… ready to limp down the stairs for work tomorrow. It’s such a tough commute to my home office!

I guess now I’m writing my final notebook entry for this trip. I’m already packing after collecting digital pictures all over the area, and the sun is high over Sphinx Rock. It will be noon in a couple of hours. I’m down at the Beater Cedar again, humming “Until We Meet Again.” It has remained mostly overcast all morning, and will probably stay that way for a while. Meanwhile, it’s keeping the heat down nicely. Even though my pack was lighter than it has been in over 40 years, I still brought a lot of stuff I didn’t use: the tent fly, a sketchbook & pens (I didn’t feel like drawing), a book (I didn’t feel like reading either), two dehydrated meals in foil pouches, one extra dried soup mix, and too much beef jerky. There is leftover coffee too, but it is reassuring to the spirit to have plenty of coffee. I also brought a hooded sweatshirt I wore only for an hour, but it made a splendid pillow all folded up and tucked inside its own hood. All things considered, I did pretty well in bringing “the bear necessities” of life. Next time, I bet I can lighten my pack down to 25 lbs., easy. Overall, I didn’t sleep too well, but that seems to be my normal pattern while backpacking. I can sleep when I get home (in more ways than one).

My exit route will take me up the foot of Dat Butte, from which I hope to photograph some cool angles of the basin that I don’t yet have in my collection. I recall tracing that route on Google Maps back home, and deducing that it holds its elevation rather well. The Google Maps software has opened new insights into the Bear Lakes region for me. When I plot this area on a topographical map, the terrain is flat and static, with contours and elevation suggested only by lines on paper. However, when I see them on my computer screen in Google Maps, the terrain comes alive in simulated 3-D. I can see the flow path of the ancient glacier as it inched its way down to the Trinity River valley. I can see that the glacier flowed directly towards Mt. Shasta, just as the valley still points to it today. The peak of Mt. Shasta lies roughly 30 miles east-by-northeast from The Altar. When visibility is not compromised by smoke or weather, her details are sharp and clear. How much stronger are her messages that cannot be seen by the eye! The two localities seem interconnected somehow, in the same synergy by which all sister volcanoes in the region once shared their power with the great Queen Shasta.

It’s fascinating to use Google Maps to look at Mt. Shasta itself. The software makes it easy to discern huge bulges from ancient lava flows that now form the shoulders of the great mountain. Zoom out to view it from a grand geologic scale, and the entire structure looks like a melted candle stub… except that the “wick” is over 14,000 feet tall. I wonder, how high was the original candle? The tapered volcanic cone that forms the rim of the Bear Lakes basin also becomes clear in 3-D. Its edges are sharply defined, and stay nearly level at about 7,000 feet for over 5 linear miles, tracing 80% of a circle around the lakes. The great volcano that once exploded, leaving behind these blown-out edges, hanging cirques, and glaciers must have been over 10,000 feet tall!

The mysterious Mt. Shasta has been the subject of much speculation over the centuries, from New Age myths, to UFOs and Bigfoot, and fantastic tales about lost races and tunnels under the mountain. It has been a sacred focal point since ancient times; for as long as there have been humans to cast eyes upon it. Verily, it is considered to be one of the 7 holy mountains in the world by the Buddhists who have built a monastery on its slopes. And when standing at the Altar next to Wee Bear Lake in the Trinity Alps on the Summer Solstice, the sun rises directly over its summit. How could this arrangement not be extremely significant?

So, how did The Altar get there? Geology informs us that the Altar and its remarkable companion boulders were left strewn at the edge of a great moraine formed by the glacier that once scoured the valley. Their improbable location at the cusp of a promontory was entirely due to chance. However, as any honest geologist will tell you, we are able to postulate the effects of the gargantuan energies that formed this planet much better than we are able to understand the causes.

What God would not want to build an altar from which she could be recognized and admired? If the universe has the ability to create life and evolve humans so that it might be able to contemplate itself, would it not also provide sacred viewing platforms? The placement of the Altar is not entirely arbitrary as geology suggests, and it is definitely not subtle. It’s a gob smack; an in-your-face reminder that there are far greater forces at work on this planet than any “ology” could measure.

“Once upon a time I was an ocean, but now I’m a mountain range.

Something unstoppable set into motion.

Nothing is different, but everything has changed.”

— Paul Simon