“You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

For a hundred miles through the desert, repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile, the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese high in the clear blue air

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting –

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.”

— Mary Oliver

I graduated from High School before I finally figured out how to visit the Bear Lakes properly. Chris, my close friend from Lagunitas and a year behind me in school, had accompanied me on many local hikes up Mt. Barnabe and the Bolinas ridge around Kent Lake. We became daringly adventurous in the hills near our homes, launching long forays on dirt fire roads and side tracks, exploring every tawny hill and dark, laurel-choked canyon. We fostered a spirit of becoming one with the landscape by climbing to the tops of 90-foot redwoods, jumping from tree to tree like squirrels, and leaping down bold shortcuts in the ravines. Naturally, my tales of Big Bear Lake entered the agenda of our intrepid little expedition company, and Chris was eager to see the lakes for himself at the next possible opportunity.

Chris was a tall, athletic, rangy fellow, brashly sure of himself and his worldview. He liked to have different opinions and interests than other people, and fancied himself a unique character. He lived benignly in the fragmented fantasy world commonly constructed by sensitive children of divorced parents, and painfully forged a nonconformist reputation at school. He espoused sex, drugs, and rock & roll when he needed to fit in somehow, but he was more comfortable in the wild, unexplored Middle Earth of Tolkien than in the stultifying, conventional classrooms of planet earth. We shared a love of cartooning, eclectic music, irrational hopes, and underground humor, and became inseparable friends while avoiding toxic, irrational institutions as much as possible.

Due to my graduation and Chris’ work obligations, we didn’t get around to organizing our trip until September, but we planned to stay a full four days to make up for the delays. Everything about the expedition was meticulously charted and considered, from cassettes especially made for the long drive up Highway 5, to scrupulous attention to the weight and utility of every item to be carried in our backpacks. I had the privilege of discovering Colin Fletcher’s The Complete Walker, a wise, classic treatise on sensible backpacking and the origin of the saying: “Look after the ounces and the pounds will take care of themselves.” Back in the seventies we had a diverse camping store available called Marin Surplus, which stocked various and sundry paraphernalia of outdoor necessity and extravagance. In the early days you could get surplus K-Rations from the Vietnam War, a Boy Scout compass, white gas stoves, inflatable rubber boats, Italian hiking boots, streamlined nylon backpacks, ultra-light sleeping bags filled with Norwegian goose down, amazingly light foil pouches of dehydrated food, used U.S. Army clothing and field gear, and even slick astronaut food from NASA. With our budget, we opted for a minimalist approach to lightening the load, and spent our hard-earned dollars on a carefully selected menu of dehydrated food. To compensate for the uniformity of the sterile-looking pouches, we experimented with dried, lightweight items from a local Asian market as well, which led to a gourmet appreciation for Cup O’ Noodles, and a visceral aversion for musty dried mushrooms (unless they had hallucinogenic qualities, which will be explained later).

My older sister Judy joined us for this trip, along with her dogs Che and Shirelle. She had made little saddlebag backpacks for them so they could carry their own food and water. These were tested on a few day hikes in the local hills, and was looking forward to the novelty and practicality of the venture. We all piled in one car this time, a rusted hulk of Detroit muscle we called “The Beast,” which used to be a Barracuda back when anyone cared. The entire drive up was agreeable and uneventful, and the soundtrack was outstanding. Joe Walsh and the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band mixed in unexpected ways with scalding Rush and Les Dudek tunes, all of which made the drive fly pleasingly by. We forced ourselves to slow down and take our time on the drive, and made a few stops along the way to ease the monotony.

One regular stop for us on the droning gray ribbon of Highway 5 was Maggie’s Drive-In in the country town of Williams. This sun-blasted aluminum lunch counter made a greasy spoon look like fine polished silver. The corpulent burgers would still be popping and sizzling when served in a slippery plastic basket on a glistening pile of crisp onion rings. As one hand ponderously maneuvered the dripping burger edges for choice bites, the other hand waved the clouds of flies away. Add to this the milk shakes too thick for a straw, and we had a king’s turgid Medieval feast; a veritable Nirvana of gastronomical coagulants. This gluttonous glob clogged our stomachs for hours like wet cement, but we had nothing else to do but belch and fart anyway, while driving past one desiccated field after another. We made another curious stop in Corning, to peruse the garish, fluorescent olive tasting bars that were advertised to screaming redundancy on evenly spaced highway billboards. Then again in Weaverville, we filled the belly of the Beast with hot gasoline vapors (and our own bellies with more junk food that produced a similar internal combustion). This was what our discerning palates chose as a proverbial “last meal” before adopting an even scarier diet of gorp, dehydrated Chili Mac, and salty Cup O’Noodles for four days.

We decided to save time and money by camping at the trail head, which increased our chances of actually achieving an early start the next morning. This turned out to be a success for once, and we were ready at dawn to leave civilization for the longest backpacking trip any of us had ever attempted: four days with no mommies to tuck us in. We wanted to start small, and build up our experience and appetite for extended wilderness survival. Generally, the length of time one might backpack in reasonable comfort and nourishment is limited by how much stuff one is able to carry. In our novitiate insecurity, we brought way too much gear and supplies for a mere four days, probably due to all the “detailed planning.” Imagine our chagrin when we found that we had to provide the energy to leverage every ounce of “we might need this” and “you never know” up 3,500 feet of rocky trail with sheer muscle and willpower; as punishment for our excess of caution.

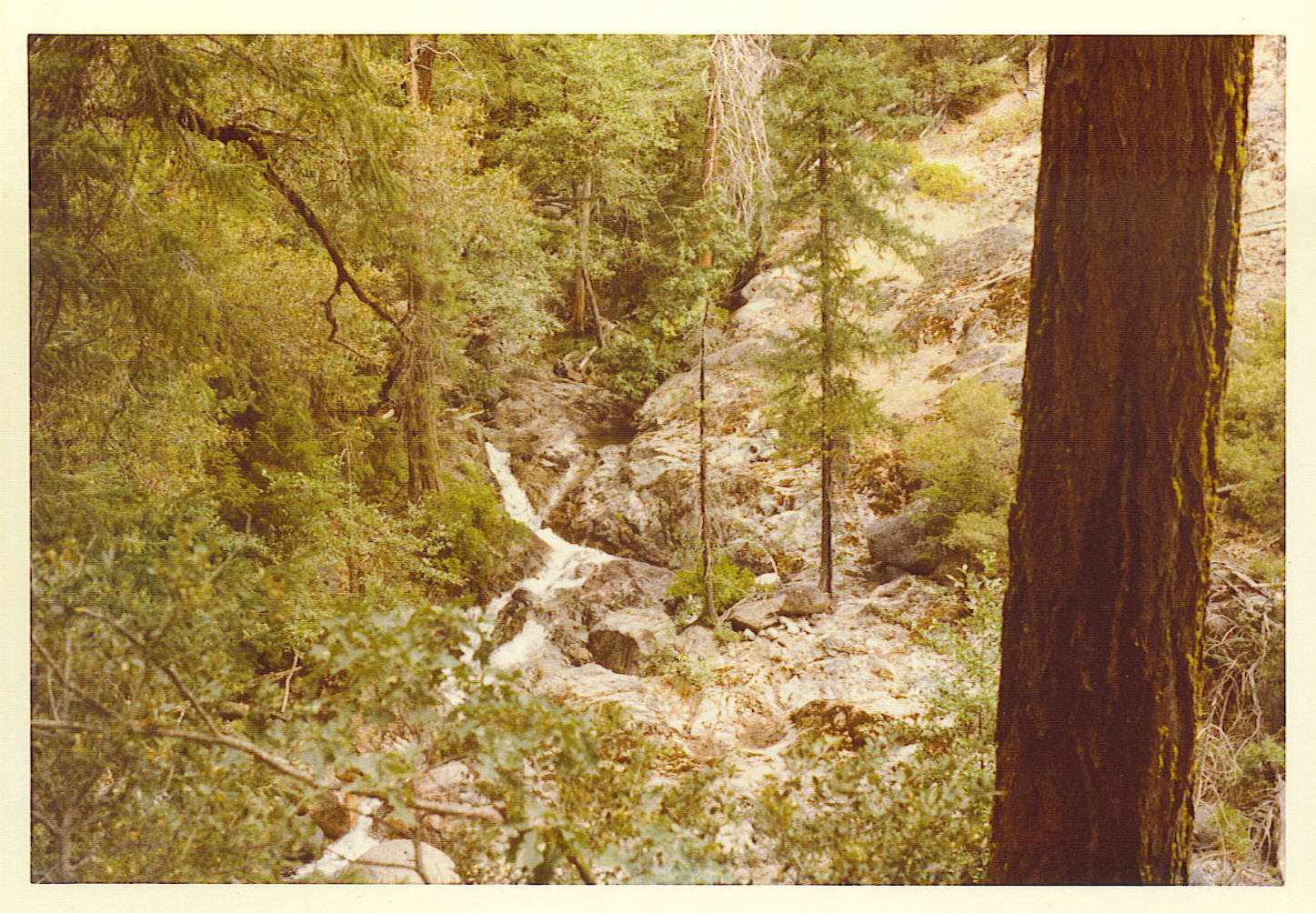

Our early start, combined with our deliberate choice not to be in a hurry, made the trail experience much more enjoyable. It helped that the dogs’ new saddle bags slowed them down to a plodding acceptance like beasts of burden. In the cool morning hours, we got the worst of the trail out of the way before the sun peeked over our shoulders well after mounting the westerly ridge to Big Bear Lake. As a result, we noticed more details and the beautiful country surrounding the trail. Before, we had dismissively cursed the rocky, crusty first part of the trail before the bridge. This time, we leisurely noticed that Bear Creek splashed happily among rounded boulders, beautiful pools, and miniature waterfalls all along the trail. We stopped to rest frequently, beginning with the old Forest Service bridge made of retired telephone poles that thrust stiffly over the steep, fern-lined creek bed. A cute little waterfall burbled a greeting as it plunged into a lucid pool large enough for a cool dip. Majestic, towering Ponderosa pines swayed dizzyingly high above a leafed canopy of alders rattling softly with autumn dryness and color. The trail turned out not to be a rapid conquest or an ordeal to endure, but a pleasurable stroll through a gallery of landscape paintings in nature’s own art museum.

After a pack-off rest, we resumed providing the energy for moving mass up an inclined plane: essentially, up the side of a damn mountain! The official backpacking physics equation for this is: E = MC2. Using words, this translates to: Elevation = Mass (backpack) times Calories (squared). Despite the harsh lessons of gravity, we settled into a trance-like, rhythmic expenditure of energy. Even the dusty, steep switchbacks after the bridge began to take on a rustic charm when viewed at a reasonable pace. The black oaks stood their ground with a charismatic sort of scruffiness. An array of curious blue-gray boulders with comical, ill-fitting toupees of moss winked in the first amber rays of the sun. Toiling as heavily laden workers up the side of an anthill was never so enjoyable.

Adding to our pleasure, we found that the worst part of the trail had been improved by volunteers or unknown USFS angels earlier in the year. The ascent was rerouted intelligently, with the old route already growing back in behind the roped-off turn. The scratchy, grabbing scrub manzanita were curtly chopped back and thinned out, in a vigorous effort that looked a bit severe at first, but would rapidly grow back to hide the roots and stumps. We silently, sincerely praised the hands that sweated and bled to make our passage easier. What a noble, unselfish endeavor! What appropriate use of taxpayers’ dollars! Would they come back and carry our packs for us, too?

As the trail leveled out slightly after gaining the ridge, we noticed how profoundly the soil and flora changed along the trail. The manzanita and scrub brush thinned out as a sparse mixture of black oak, cedar, and Jeffrey pine began to take over. An occasional dogwood or alder competed for space as the trail meandered along the ridge, gaining elevation wherever possible. The creek we left behind at the bridge began to sidle up to the trail, getting louder in the clearings until it sounded only a few hundred feet away. This was a handy spot for another pack-off rest and filling water bottles. The dogs’ packs appeared to be holding up all right, as they panted and snapped at horseflies in the shade. Those particularly evil insects were large and fast, with creepy, banded green eyes that bugged out when they landed. They zoomed in great arcs, and tried to skewer your leg like a dart hitting the bull’s eye. I tracked one of them like a curveball, and whacked it hard to deep left field with my palm.

I had a new addition to my camping gear that was proving to be very useful. We had bought a rug some months before that came with a stout 6-foot bamboo pole rolled up inside, about an inch in diameter. Light and strong, and naturally balanced, it seemed too unsubstantial to serve as a stout staff until I fastened a cone-shaped rubber dog toy on one end. This somehow transformed it from balance to energy. When I tried it around the Lagunitas trails, the weighted rubber had a pendulum effect that metered the walking stride. This same technique, now applied to the flat parts of the Bear Lake trail, was working well at first, but the rubber cone was often slipping in the gravel. So I reversed it with the rubber cone on top, and the blunt end of the stick dug in to the rocky trail soundly. The whole idea was to employ the arm muscles somehow in the vertical leveraging of weight vs. gravity, and it was working! I could feel the assistance like a third leg in spots, as the extra push of the walking stick boosted me up one boulder step after another.

The stick had another advantage in the clearings between forest glades, where the thick tangles of ferns, grasses, flowers, vines, and shrubbery crowded the trail. I learned to lay the stick forward at an angle, and plow the foliage aside as I walked by, and this could be timed with a well-placed push off the stick. I was really appreciating my bamboo invention, and when the trail started to scratch through old avalanche slopes of boulders and tumbled rocks, I discovered an added bonus. With the rubber cone on the bottom again, the stick found secure purchase on the rock faces, and eased the in-between and downward steps that added so much to fatigue. Back in the forests, as the trail switched repeatedly from one terrain to another, the rubber cone resumed its pendulum swing, and seemed to eat up the ground with rhythmic strides. Add to this the many uses around camp for a 6-foot pole, and this was easily the most versatile and useful item I had ever brought backpacking. Best of all, its weight didn’t count because I carried it in my hand and not on my back!

Even as we toiled, we noticed that the forest glades tucked into the dells and valleys along the ridge were rich with autumn color. The dusty green shades of the evergreens contrasted brilliantly with red, orange, and yellow leaves of the trees that were giving their hard-earned leaf mass back to the earth. There were often strange juxtapositions of spring-like flowers, lush new growth, butterflies, and bumblebees in the moist, shaded hollows where until late snow had remained. Right next to these little gardens would be a small mountain hemlock, an alder in blazing autumn color, or the bracken and dried vines left over from a summer orgy of plant life. Ceanotha, western azalea, and huckleberry shrubs were in fall splendor too, and the manzanita berries glowed brilliant red. We were enjoying the leisurely pace again, and marveling at the hundreds of picturesque displays of plants and alpine forest dioramas that heretofore had passed unnoticed by sweaty, impatient eyes that sought only for the next resting spot.

“Walk as if you are kissing the earth with your feet.”

— Thich Nhat Hanh

In this pleasant, unhurried way we made significant progress by late morning, and avoided the hottest parts of the trail during the times when the sun beamed straight down through the trees. Ol’ Sol was lower in the sky this late in the year and this also helped keep the temperature comfortable, although he was fierce and hungry when he got an open shot at us. It took 4 hours to get to the most magnificent part of the trail where it exploded with granite views all around, but we were still feeling fresh and unhindered by the typical blind lust to get to the lake as fast as possible. We had reached the point where we could see the entire way up the mountain to the cleft 1,000 feet above where I knew Wee Bear perched like a falcon ready to take flight. We pointed and picked out imaginary routes up the seemingly endless ledges, to determine if there was a possible short cut. I reminded Chris and Judy again about my harrowing experience with “short cuts” on that same mountain face with Rob and Dave 2 years before, and we marveled at how any of us made it down alive, for the rock faces were stained with waterfall marks and choked with brush, and it looked so unreal and far, like a faded postcard of the Grand Canyon. We prudently decided to stick with the trail and gain altitude the sensible way, plodding like cows instead of daring to go where eagles fly.

This was the part of the trail where the jagged edges of the Sawtooth ridge began to poke through the treetops to the north. From this angle the formations loomed above us like a massive museum display of gods and idols flung against an impossibly azure sky. Ahead to the west was a humongous head of an eagle, with granite wings stretched out for hundreds of yards. Over our right shoulders a grizzled bear-man’s head stared protectively out over the valley. In the middle clustered a group of granite gossips: long, leaning female demigods who appeared to be looking down and whispering about us. Everywhere along the crest, isolated stone pinnacles stood as if they were frozen statues of giants that once roamed the trail. Far below, chunks of broken granite ranging from the size of mansions down to a small car were strewn about as if they had been flung carelessly by these deities, whose countenance was so stern and regal we bowed under our loads and averted our eyes instinctively. With a nod to our old friend Tolkien, we reverently referred to this part of the ridge as “Beorn’s Lair.”

Soon we reached the large avalanche washout, where the small trees were making a comeback and the scattered boulders were already smaller than I remembered, as the surrounding brush had grown up to conceal their bases. Here was the spot where one could conceivably cross Bear Creek and zigzag up the stepped pyramid face of granite ledges that led to Wee Bear and Little Bear. We took another rest and explored the deep channels and gorges where Bear Creek still bustled in the depths. There was enough melting snow this late in the year, concealed deep in the cracks and crevices around the lakes, so that the outlet creek remained full and lively. Chris’ head was on a swivel the entire time, craning his neck around the whole panoramic sweep of the basin, astonished at the overwhelming grandeur and majesty of the saw tooth ridge and glacial cirques. Judy and I had seen this before, and had been dreaming of this time when we would see it again through the eyes of a newbie. It was as if we, too, were seeing it fresh and new for the first time: this garden of delights that God had made especially for us. Equally refreshing were the people we saw coming down the trail who were leaving. “Yes!” we exulted selfishly, knowing there would be at least one unoccupied campsite. We had chosen the end of Labor Day weekend to hike up, expecting that many people would be leaving and we’d have the lakes to ourselves. There had been a few dusty cars parked back at the trail head, but not as many as we had feared.

“Wow, you guys made it up this far already?” a fresh-looking young woman asked, and she passed with a man and another couple, going back down the trail. It still wasn’t noon, and we were almost to Big Bear Lake.

“We got an early start,” we replied conversationally, and happily waved them on down the trail out of sight. The lake was soon to be ours and ours alone!

“They might have two of those cars down there, so there can’t be many people left,” Chris calculated out loud.

When we reached the wide, smooth granite slabs where Bear Creek flattened out and scooted over the hot granite in cool sheets, I urged another pack off rest, even though we were now so close to the lake. I wanted to try something I had always thought about. One particular stretch of shallow flow had the appearance of a water slide, and I took off everything but shorts and gave it a try. It wasn’t exactly the way I had imagined, but I could kind of walk my buttocks down the rock and plop in the lower puddle, wriggling like a clumsy tadpole. But the water was nice and cool, and we all got a laugh. We stashed our packs nearby so we could make a brief detour to the lower lake.

Our stay at Big Bear Lake was indeed short and out of our way. The best way to get to Little Bear Lake was to traverse upward from the water slide flats, and pick a route through the rugged crags until mounting the south-facing ridge to Little Bear. It was only a few hundred feet of vertical gain from there, and there were rock cairns pointing the way. But first, we wanted Chris to see the lower lake in all its glory, as a prelude to the even more glorious higher lakes. Big Bear Lake had lost its morning brilliance by this time, but the noon sun still sparkled like a hundred thousand diamonds on the water. The great craggy peaks around the rim of the lake stood out in stark, silent relief against an azure sky like I remembered, and the green swards of brush rippled lush and verdant up the mountain flanks. Chris gazed slack-jawed and thoroughly impressed at the splendorous spectacle, as I told him for the hundredth time, “Wait ‘til you see Little Bear.”

“You’re right,” he breathed in awestruck appreciation. “The pictures don’t do it justice.”

“Mountains should be climbed with as little effort as possible and without desire. The reality of your own nature should determine the speed. If you become restless, speed up. If you become winded, slow down. You climb the mountain in an equilibrium between restlessness and exhaustion. Then, when you’re no longer thinking ahead, each footstep isn’t just a means to an end but a unique event in itself. This leaf has jagged edges. This rock looks loose. From this place the snow is less visible, even though closer. These are things you should notice anyway. To live only for some future goal is shallow.

It’s the sides of a mountain which sustain life, not the top.”

— Robert Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance