Lunchtime was a bigger deal than in previous expeditions. Boys like to eat, and meals are the events by which a day is measured. I demonstrated the wonders of reconstituting freeze-dried food for the novice campers, who insisted on preparing their own packages. Kevin kept opening his package of Chili Mac to see how it was progressing, and Judy couldn’t resist a course correction. “Leave it alone, you’ll ruin it,” was her tactful advice.

“It’s my food, leave me alone,” came the loving response.

Logan sat staring at his silver pouch of beef teriyaki, as if he was waiting for the familiar “ding!” of a microwave. I opted for a Cup O’ Noodles. I rarely ate such processed fare at home, but something about backpacking demanded foodstuff that cooked itself. I added a handful of ‘Just Veggies,’ which was health-food-speak for freeze dried vegetables with nothing added. I had been loosely practicing a semi-vegetarian diet for nearly 15 years. Judy doubtfully stirred a gooey pouch full of something labeled “Lasagna” that threatened to crawl out and attack her at any second. The dogs watched every movement carefully, with the intense concentration of air traffic controllers.

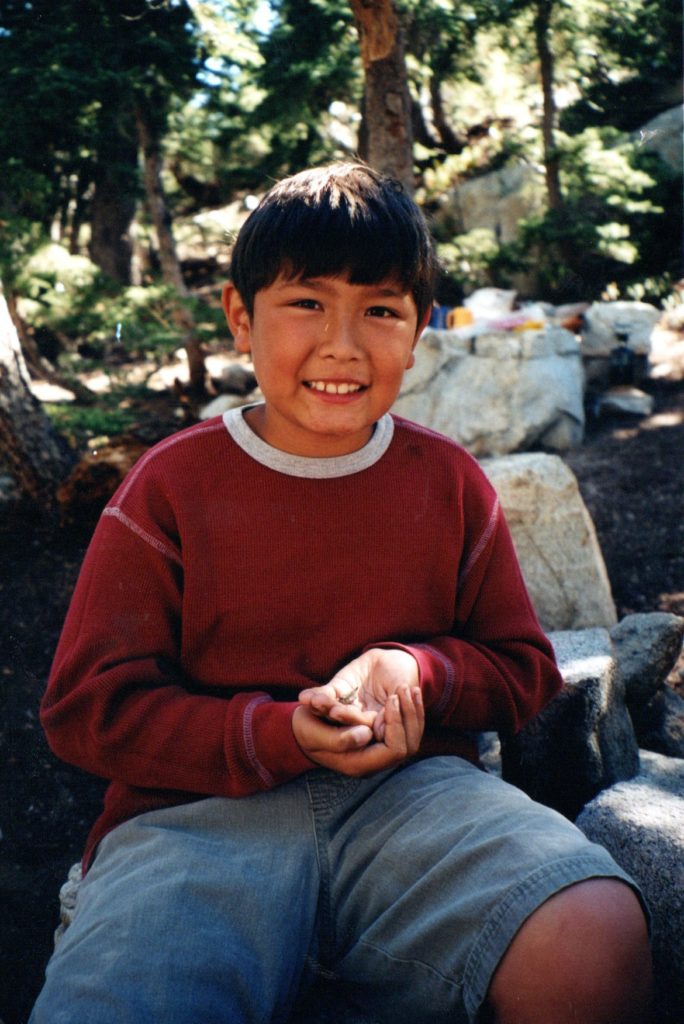

“Ding!” I yelled, and Logan jumped. We all laughed. I wish the food had been as good as the company, or the day, but all that mattered was refueling for the next adventure. “What do you guys wanna do after lunch?” I asked in an indulgent tone of voice.

“Let’s try fishing down at the little lake,” Kevin suggested obsessively.

“Yeah, the fish are probably closer together,” added Logan brightly, as if expounding on a universal truth. Kevin stared at him, wondering if there was a veiled insult.

Of course, the implication was that if the boys wanted to explore Wee Bear, the parental units would have to come along too. Oh well, we had nothing better to do. For me, that was the main reason for backpacking – having nothing better to do than to get to know your surroundings once you arrived at your destination. I liked the immersion of being in one place for a long time, and communing with the landscape intimately. Unlike the hurried childhood military campaigns that my dad forced upon us in the guise of “camping.” There are legendary backpackers like Colin Fletcher, whose linear conquests of vast stretches of wilderness are truly impressive. I preferred the Thoreau method of getting to know one’s surroundings intimately. To me, that was the meaningful conquest: to know the landscape well enough to truly understand one’s place in it.

We secured the campsite against varmints, and relocated a few hundred yards east for the afternoon, in one of the most amazing landscapes I have ever encountered. I have been to Yosemite, and of course that valley has a singular place in the DNA of any nature lover. I have stared at the Grand Canyon, knowing it to be an impossibility. I have also been to most of the major National Parks in the United States, and they are all admirably picturesque. But the area around Wee Bear Lake in the Trinity Alps of Northern California is so incredibly scenic that it defies adequate description. Until you have actually been there, you cannot make any meaningful judgment. Photographs are tantalizing, but can only tell part of the story. Everywhere one looks, one is flooded with astonishing panoramas that enhance one’s sense of actually being there. The perception of looking at any single scene is amplified by all the other scenes crowding the senses. The sheer intimacy of the landscape cozies the mind like a sleeping bag, and the grandeur boggles the brain’s ability to process visual information, until one simply surrenders into the loving arms of the mountains.

The boys went right to the best fishing spot, and renewed their banter about who would control the pole. I made a mental note to always bring at least one set of fishing gear per child from now on. The peace would be worth the extra weight! Judy and the dogs moved across the small lake to the steps of Dat Butte, where there were many flat, scenic spots for relaxing in sun or shade. I went directly to the Furniture of the Gods, where the greatest variety of spectacular views was focused. Standing on “the couch,” I gawked at the many faces of Sawtooth to the north, and marveled for the hundredth time how it looked close enough to reach out and pinch its granite cheeks, or trace the rocky lines of its aged wrinkles. Off to the east, the many moods of Mt. Shasta were obscured for the moment by a smear of featureless clouds that blotched out the horizon. These were probably the ruffians that had tried to rain on us the night before. The broad valley stretched out dreamily below my feet, with its green shag carpet of trees. The ceaseless updraft brought a warm bouquet of evergreen that cleansed my skin and ruffled my hair. I turned south and to my right, and the towering, regal visages of Sphinx Rock gazed away northward over my head, as if wistfully following the summer flight paths of wild geese.

I turned back to Wee Bear, and the ones I loved, and the circle was complete.

The circle represents life to Native American tribes, and I have often reflected on the wisdom of this symbol. To perceive the surrounding circle, one must be in the center. There can be no circle without a center, and no center without a circle. The great wheel of human life begins as a child, and ends as a child, and the One at the hub watches the entire cycle. Each and every watcher is the heart of its own universe. Within and without this sacred hoop, uncountable planets, galaxies, and universes all travel in circles, dancing with allurement to one another. Gravity is the powerful spherical pull of non-physical attraction manifest in the physical universe. I stood there transfixed, overwhelmed by all the love that was pouring into my center through my connection with the circle, and my sensibilities were distilled to the very essence of existence, which is gratitude. I knew that my loved ones were satellites orbiting my attraction, and that despite my erroneous exploitation of this affection, the circle flowed on unchanged. I humbly thanked the Great Spirit for this day, and for the opportunity to learn.

My reverie was broken by shouting and splashing from Wee Bear. “What happened?!” I called across the tiny lake.

“Logan dropped my pole in the water!”

“No I didn’t, you grabbed it from me!”

“Well, go in and get it!”

“I’m not going down there – it’s your pole!”

This was the level of conversation prompted by pure emotion, where the higher brain took a back seat and watched the primitive limbic system drive over the cliff. By the time I got there, they were both ready to either cry or push someone in the water. The splashing was from Jesse, who had jumped (or been pushed) into the lake in a vain attempt to retrieve the stick – I mean pole. “Do you have any line left?” I asked calmly, with a greasepaint smile.

“Um, yeah it’s over here,” Kevin sniffed, happy to consider a chance not to get wet.

“Let’s put a hook and weight on it, and snag your pole to drag it out,” I suggested.

The boyish enthusiasm returned, and resulted in arguing about who would be the one to hook the pole. “Tell you what, we have enough here to make two lines. Kevin, it’s your pole, so you get the best spot. Logan will go over there, and whoever drags the pole out first gets to use it for a long time.” Oh, they liked that idea very much, and shifted the banter to taunts and boasts about the best stick, and who would get it first. I prepared the lines, as they each fine-tuned their au natural casting equipment.

“When I say go, start tying your line on the stick,” I spoke like a reality show host. “You may want to take your time and tie it on well, because if it comes off, you lose.”

Judy had come over to see what was going on, and James panted slowly behind, wishing he could take off his fur coat.

“Go!”

The frantic tying and casting commenced with alacrity. The lake was only about 15 feet deep at the most, and the pole was submerged halfway down the cliff face formed by the large outcropping on which we stood. The rock had two natural promontories like rounded bows of twin boats. Kevin grasped one of these with his knees and one arm, as he whipped his pole to try and get the tackle close. Logan stood on his tiptoes on the other knob, waving his shorter pole like a baton. He reminded me of Mickey Mouse in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Jesse barked at all the excitement, leaning over the edge and considering another jump.

“No, Jesse!” Splash! He couldn’t resist.

“Stop! You might hook the dog!” Judy yelled and took control. Kevin yelled back. James barked. Jesse paddled frantically and looked guilty at the same time.

When I could stop laughing, I yelled, “Time out! Time out!”

Eventually the yelling and splashing abated, and the surface of the water slowly returned to transparency. “I think I got it!” Kevin exclaimed, and sure enough – the pole moved!

“Oh man, my stick’s too short!” whined Logan.

Kevin carefully shifted position through some baby trees, and coaxed the tip of the pole out of the water. The heavy end with the reel stayed down. It looked like Kevin’s hook had caught the other line; not the pole. He wrapped the new line around his hand until he could grab the old line, and from there he pulled hand over hand and seemed to be gathering only the lighter fishing line. Finally, he gained some drag and the pole came all the way out. He looked like a silly cartoon character balancing impossibly on a cliff edge, with great snarled loops of line all around him like clouds. He reached over, grasped the tip, and pulled it triumphantly. Snap! The tip broke, but the pole was already out of the water. Despondently, he surveyed the cards of his bust hand, and decided to bluff.

“I didn’t want to go fishing anyway. I’ll race you to the bear cave!” The boys took off in a new direction, leaving Judy and I to collect the hooks, lines, and pieces of the pole. She started to call them back to clean up, but I shushed her and got to work. I was too pleased by the boys’ happy diversion of negative energy to be enforcing any “rules.”

Back at camp, I set about mending Kevin’s fishing pole as best I could, and salvaging the good parts of the line we collected. Only the tip broke off the rod, which would definitely hurt its casting ability, but there was still a three-foot length that was serviceable, and many yards of line. The mess that was too snarled, or tangled in twigs, I stuffed into our “pack it out” bag. In the momentary quiet before they returned from the cave to look for something to eat (what else), I recalled the times I had gone fishing during the summer when I was a boy. Most often, it was a safety pin hook on a makeshift pole of some sort. My friends and I would ride our bikes a couple of miles; from our suburban homes up on the steep, tawny hills of Terra Linda, down to where Miller Creek still flowed timidly through the drainage projects and construction debris. There remained a few shocked live oaks and thin, weedy bay laurels down there, hardy trees that could adapt well to human infestation. There was also one big fishing hole where eager fingerlings could be hooked with little preparation or effort.

It wasn’t so much the fishing that was the attraction, but the freedom. Folks never seemed to question us much if we had fishing poles. “It’s just a bunch of kids going fishing; leave ‘em alone.” We all went “fishing” as often as possible – mostly as a justifiable way to stay away from our families. The kids my age who hung out together shared the common, silent trauma of a dysfunctional domicile. The curfew edict was usually, “be home before dark,” and summer days gave us longer relief from the raging psychological battlefields. The long, summer days blessedly took their time getting dark; too, but sometimes we waited too long. Depending on the mood back at headquarters, we tried to plead that it wasn’t really dark if we could find our way home. This usually met with little success, and the next day we knew someone had been wounded.

“Where’s Steve?”

“His mom said he’s grounded.”

And so it went, in the dismal trenches of the Suburban Front. Children were drafted into an unexpected foray, wide eyed and innocent, equipped with only the basic tools for battle. We had to fend for ourselves against entrenched, experienced tyrants of torment and injustice. Eventually, we learned how to use our weapons, but it was a lifelong conflict. War-scarred soldiers are not the only ones vulnerable to the disorder known to result from prolonged, traumatic stress! PTSD is commonly recognized nowadays, but back then, the kind we got was hidden behind the fancy doors of single-family homes with sparkling blue swimming pools. Social workers and therapists were almost never an acceptable option. Seeking “treatment” was a kind of permanent stigma for a white, middle-class family, like converting to Judaism, or being wiped out in a fire. When it happened, it was obliquely referred to as “having a nervous breakdown,” and was a sure way to have one’s membership at the country club revoked. So, the war raged on for generations, and nobody asked why, for fear of being culled as a “weak link” by the pack. Judy and I were not the only survivors, but I think we were some of the few who lived to at least recognize the signs of psychological abuse in our own lives, and we learned to deal with it in different ways. My way wasn’t very successful. I tried to quarantine all my bad behaviors and self-correct them, and wound up living two very opposite lives.

Up here, at least, I could relax and let my good side play in the forest. I inspected the fishing rod repair, and reeled in the line just in time for the boys to come back. “You fixed it?” asked Kevin incredulously.

“Not really, but I’ll bet we can catch a fish tonight when it starts to get dark.” I laid aside the broken pole with my forlorn memories, to see if they might be of some use later.

“When I call to mind my earliest impressions, I wonder whether the process

ordinarily referred to as growing up is not actually a process of growing down;

whether experience, so much touted among adults as the thing children lack,

is not actually a progressive dilution of the essentials by the trivialities of living.”

— Aldo Leopold