you are aware of the whole environment

as well as the cup of tea.

You can therefore trust what you are doing;

you are not threatened by anything.

You have room to dance in the space,

and this makes it a creative situation.

This space is open to you.”

– Chogyam Trugpa

The threatening clouds of the day before turned out to be wimpy fog that melted away when the morning sun rose above the high tip of Dat Butte behind us. What would we do with this day? I had purposely not made any plans whatsoever. I wanted the day to unfold like the Halcyon summer days of my boyhood, when nobody bothered me and I could do anything I wanted. I have always been what Judy calls a “clinker,” which is one who must have something in one’s hands nearly all the time, and is constantly clinking it against a rock, or throwing it, or seeing what one can make from it. Of course, I often did this just to annoy her. Nonetheless, I had a blessed talent for never being bored, ever. I could take a twig and a blade of grass and amuse myself on a small scale for a long time. Or just sit and look at things. My mom took a picture of me as a boy on our cross-country car camping trip, just sitting on a large rock in the desert and looking. I wish now that I knew what was going through my mind when that picture was taken, unbeknownst to me.

Today, of all days, I wanted the boy agenda to rule. No more “let’s hike there” or “You wanna see something cool?” This was a day for the children to lead the adults back to an age when the days lasted three times as long, and the biggest responsibility was remembering to tie your shoes.

Predictably, Kevin wrestled his fishing gear from his pack, and studiously pieced together his pole to test the waters. Logan tried to read one of his books, but the outer sensory extravaganza was too overpowering. I was happy to see that by the time I had finished cleaning up after breakfast, he was drawn to the lake shore with Kevin and the dogs. He followed Kevin around the fisherman’s trail at the edge of the lake, and tried to get a turn holding the pole. Judy produced her own book from somewhere within the mysterious female depths of her pack, and staked out the prime spot at the top of White Bear Rock, where she could serenely sunbathe and watch everything. True to my plan to have no plans, I did nothing more ambitious than poking at the rocks near the shoreline with a stick. My sense of parental responsibility kept me within earshot of the boys, until this slowly relaxed and gave way to an emerging sense of childlike wonder at my idyllic surroundings.

I imagined I was 9 or 10 again, and had an entire summer day to flip through its picture book pages. The morning sunlight was still fresh and clear, without the hazy, second-hand look of afternoon. A blue jay hopped from branch to branch, sassing at me for existing. I ambled from rock to rock along the shoreline towards Bumblebee Spring, careful not to damage any alpine flora. The southeast side of the lake was still in shadow where the forest marched down to dark green water. I turned back to retrace my steps along the warmer, sun-bathed spots. Along the shore, I noticed how the rock was being broken into vertical slabs by winter freezing action. My stick probed the cracks to see if anything lived in them. Back home, I could always find something hiding under a rock or in a crack, and I loved to explore every square inch of a small plot of land to get a sense of what lived there. Up here, in a high-altitude climate that was supportive of life only a few months out of the year, there were far fewer creepy crawlies to entertain a boyish curiosity. I startled a couple of black beetles under a fallen log, and accidentally cut a red centipede in half beneath a granite shingle that scraped like ceramic tile when I moved it. The two pieces of its body tried frantically to run off in opposite directions. I suppose now that there was a metaphor for my life somewhere in that sad spectacle, but I was having too much fun being a boy to notice.

The wind filtered through the needles of the pines above my head with the low, keening sound of a dirge, and my high spirits faded. It’s odd how some sounds can trigger melancholia. It was just a natural chord of collective vibration caused by air molecules glancing off the edges of thousands of pine needles. When my eardrum picked up these vibrations, my brain somehow perceived the sound to be sad. Was it a memory being blown back to me from so many years ago? I recalled how lonely I had been as a child, and how little my family ever noticed. I was considered a “good boy,” because in a household full of intense drama, I rarely bothered anyone with my needs. My greatest unrequited feeling was love – especially physical affection. The unmet need was a ragged, starving hole through which a mournful wind blew almost all the time. Sometimes it felt as though my childhood had been a solitary journey through a howling wasteland of emotional deficiency. I listened to the tail of the wind as it sighed away softly up the ridge, almost as if it was cooing like a dove. There is nothing worse for a boy than to feel like he does not matter.

Suddenly, one of the impossibly huge bumblebees of the Alps buzzed my position, probably attracted by my bright red shirt. I resisted the urge to run, or shoo it away, and watched it maneuver ponderously for the best position to look at me. A couple of times I glimpsed its dark face and shiny compound eyes, no doubt confused at what they were seeing. Logan was terrified of bees, but they fascinated me so much that I often accepted them calmly instead of panicking when they came very close. Bees can sense adrenaline and it agitates them, whereas a calm observer is usually tolerated. This bee’s unlikely body was the size of a hazelnut, with a shiny, black obsidian coating. Its wings labored madly in the invisible blur of a hummingbird’s. I could see the angle of the wings adjust in relation to the bee’s body as it changed direction. On each leg, a small sack stuffed with yellow pollen told me it had likely come from the spring where the flowers were most numerous. Eventually, it grew tired of the oddity, or decided I wasn’t a huge flower after all, and it made a beeline (what else) towards the forest. I thought of following it to see if I could find its nest, but the thought of an angry swarm of oversized bumblebees dissuaded me.

A few paces later, I came upon a dazzling gem from the Trinity treasury of wildlife. An emerald green pine beetle was busy inspecting the surface of a fallen log, and I was able to get close enough to make out the joints of its antennae. Its entire body was reflecting electric green light in tiny glints, as if it wore dazzling chain mail armor. It glistened like the glittery paint that is used on hot rods and motorcycles. It was only about a half inch long, but sparkled with the splendor of the Dome of the Rock. Finally, it got tired of its fruitless search, and prepared for takeoff. I was used to seeing flies and other insects spring away in an instant, but this little guy had to go through an elaborate pre-launch checklist. First, his green wing covers raised up like twin cockpit domes, and stayed in position as the wings underneath unfolded and stretched, as flowers open to the sun. These wings had red edges that contrasted dramatically with the electric green sparkle of its body. When they started beating, the beetle held on to the log until its bulk was lifted, then it let go. With a buzz of red wings clattering against the wing covers, it careened off like a drunken helicopter pilot, to look for a more appetizing meal.

I reflected that of all the fascinating creatures I had seen during my trips to the Alps, I had never seen anything larger than an osprey. The skinny little chipmunks were the largest land animals I had ever observed. This made me laugh aloud at all the times I had trembled at the thought of man-eating bears, or thundering hooves in the night. Of course, there were deer and large predators throughout this region, but the fact I had never seen one told me they weren’t too interested in this place. The thin air and sparse nutrients at this altitude probably meant there wasn’t much return for the trouble it took for foraging animals to get up here, which naturally kept the bears, bobcats, coyotes, and mountain lions concentrated at the lower altitudes. Besides, they liked their natural diet to be augmented by the juicy trash cans and tantalizing coolers delivered by generous campers near the highway.

My wandering path had maintained a consistent radius to the location of the boys. The parental radar of responsibility was on autopilot, and kept me close enough to catch any cries for help. Hearing only the banter of argument over the fishing pole assured me that all was well. My stomach growled, and I began to think of food. What would I eat if I lived off the land like the animals? I plucked some of the grass that grew by the water, and nibbled on the end with my front teeth. Yuck. I could understand why the first people in this area decided this stuff tasted much better when processed through the warm-blooded flesh of an herbivore. Seriously, what would I eat? Chipmunks themselves wouldn’t make much of a meal, but I could compete with them for a few pine nuts. Or I could make a trout trap, basket-style, but what would I use for bait? When I really focused all my analytical powers on the problem, I concluded I would rapidly starve to death. So, I ate one of the granola bars I had in my pocket.

As I munched down the easy, processed calories made possible by commercial industry, I gazed across the lake and dreamt what it would be like to exist solely on what I could find in my environment, like the animals. We humans used to be territorial hunter-gatherers, but now we get almost everything we need by trade, cultivation, or processing. One of the most profound biological changes in our evolution was the shift from subsisting mostly on nutrients from our immediate surroundings, to consuming nearly anything from almost everywhere on the planet. We used to be an integral part of our surroundings, in that our bodies were entirely composed of molecules from the actual land around us. This made for very distinct tribes, and unique genetic mutations that were a symbiotic part of the biosphere. Now, vast populations (especially in the “developed world”) are nearly homogenous in a mosaic of molecular components gathered from nearly every corner of the globe. How has this affected the basic activity of our cells? For example, could cancer and other diseases be a form of rebellion against this unprecedented break from symbiosis?

I checked on the corkscrew tree that grows out of (or as part of) a granite knob near the lakeshore. It was stretching out hale and hearty, and was actually straightening its trunk. It looked like it had passed all its tests, and was reaching a new stage of growth. Its roots had become so much a part of the crack it was making in the rock, that it was hard to tell where tree ended and granite began. I have watched with wonder for almost 40 years as this tree struggled, grew, and learned to thrive. How much alike are I and this tree! We awoke to unfortunate circumstances, and grew up having to struggle for everything. We lacked a nourishing infrastructure of relationships to guide our development, so our early actions were twisted, and stunted our growth. We resented our inadequate surroundings, fought hard to overcome them, made many mistakes, and eventually learned how to live where we found ourselves. It wasn’t until we mastered the ability to accept the hardships and tests as the blueprints for our evolution, that we could grow straight and flourish.

I decided it was time to make a perfunctory parental appearance, and meandered back to the cove where the boys were fishing. One of the most charming aspects of this landscape was that there were so many natural pathways and conveyances: from rock, to log, to spongy ground, one may never step on a plant, or tread in the same place twice. I hailed the boys with the traditional angler’s greeting that was both a question and a tease: “Catch anything?”

“No!! Logan won’t shut up, and keeps scaring away the fish.”

“Kevin won’t let me use his pole.” Logan was waiting for an imposition of ‘fairness’ from an authority figure, since he was smaller than Kevin, and unable to get a turn by natural influence.

I used reverse psychology. “Well, it’s Kevin’s pole, and he carried it all the way up here. I guess if he doesn’t want to share it, there’s nothing you can do about it.” In my parenting arsenal, this was a loaded statement intended to fire a bullet of guilt. My own parents used to blast away like twin machine guns until the barrels melted down. I imagined myself as a nine-year-old superhero, once again deflecting lead missiles off my flat, boyish pectorals. Pa-tweeng!

“Okay, here!” Kevin thrust the pole into Logan’s hands, and stomped back to camp. “There’s no fish in there anyway! C’mon, Jesse.” I watched him go with genuine empathy. He really wasn’t being a snotty brat – this was just his way of trying to communicate in a world where his opinion rarely mattered. He knew the bullet had hit home, and resented the consequences of having a good heart and knowing the right thing to do, but having to be reminded of it.

“What are you using for bait?” I asked Logan, sitting down next to him in a friendly way.

“I dunno, some fluorescent lump that keeps falling off.” He looked at the fishing pole as if he was searching for the combination of buttons that would make a fish jump out of the water.

“Here, let me show you how Uncle Greg does it.” I took the rod and reeled in the soggy line, and discovered only a tiny fleck of Powerbait under the barb of the hook. “Where’s the bait?” Logan passed me the gaily colored jar. “You have to mold it around the hook like this, so the fish doesn’t see the hook, and it’s hard to steal.” I made a teardrop shape from the stinky, glowing goop. “Toss it out there, on the other side of the log.”

“We did that, but it got caught, and we had to use another hook.”

I explained how to let the line out, and walk around to the other side of the small cove to free the hook. “The fish like to hide under the logs and rocks at this time of day,” I offered. “They usually feed in the early morning and evening, especially at dusk.”

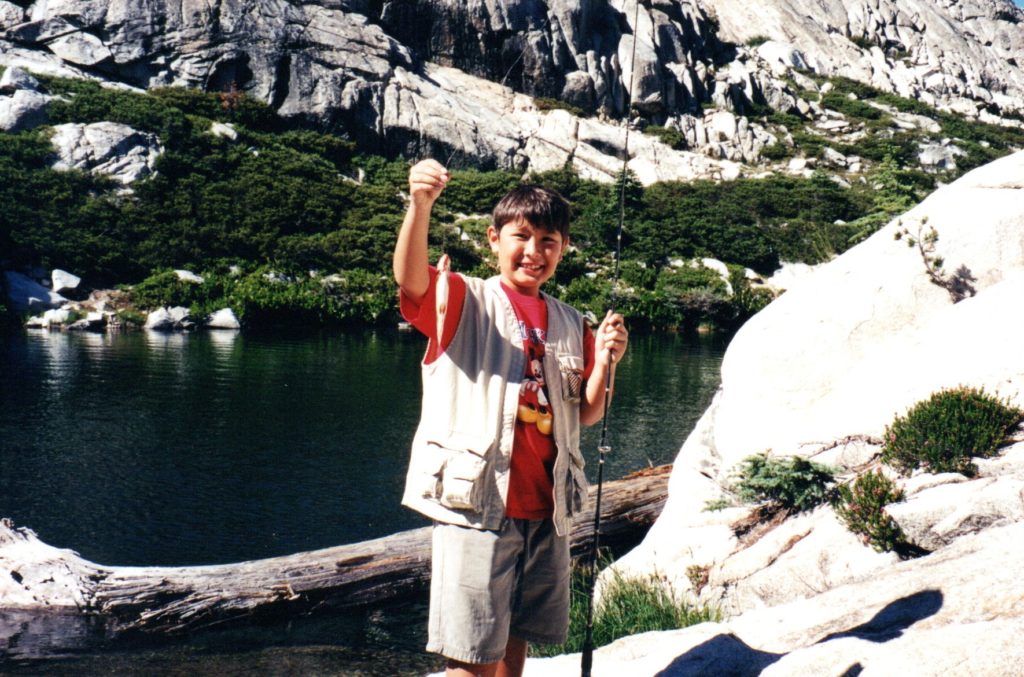

We relaxed in the blissful space of father and son sharing a moment of bonding. The morning sun had nearly reached its apex, and sparkling diamonds danced on top of the water. “I like it up here,” Logan said. “It’s pretty.” My heart melted into a fluorescent teardrop shape. Suddenly, he whooped as the rod jerked, and I helped him reel in a tiny trout! Kevin came running, greatly frustrated that Logan caught a fish, and he had not. I taught them how to remove the hook from the fish’s mouth in the least damaging way possible, and we let the little guy go… but not until after a picture! We didn’t catch anything big enough for a meal, but somehow ended our morning with a sense of being full.

“Teach all men to fish, but first teach all men to be fair. Take less, give more.

Give more of yourself, take less from the world.

Nobody owes you anything, you owe the world everything.”

— Suzy Kassem