“In this moment I saw quite clearly, that all life recedes from the tree and its leaves in autumn, the leaves become lifeless, empty husks, fall off and die. But only empty husks! The essence of life which has lived in the leaves now rests in the tree and bursts forth again in spring, clothes itself anew with a material form, and becomes leaves again, repeating its eternal cycle. The tree inhales and exhales life, and only the leaves change, only the outer shell! Life remains eternal, for life is the eternal BEING. And I saw even further: the fountain of eternal essence – human beings call it ‘GOD’ – breathes life into man, just as the Bible says that God breathed life into Adam’s nostrils. Then God inhales again, withdrawing His breath, so that the empty husk falls; the body of man dies. Yet life does not cease at this moment, it clothes itself with a new body, in an eternal cycle and moves on, as everything in this world lives and moves in rhythm, from the orbit of the planets to the breath and pulse of every living creature.”

— Elisabeth Haich

The Sunday morning chill crept up stealthily on the basin like a snow leopard. I poked my head out of my sleeping bag with the temerity of a marmot, saw my breath, and withdrew it again. There was the smell of changing weather in the air; the spell of fantastic weather was broken. Morning dew clung to all our belongings, and as soon as the sun came up, we moved them on to the flank of White Bear Rock to dry, because wet stuff is heavier to carry, it smells bad, and gets ruined when stowed away damp. We would be returning to civilization on this day, and were already looking forward to a fresh-cooked meal and a hot shower. We had the foresight to clean everything well the night before, so all it had to do was dry. We all wore layers of clothes in the cold, wet autumn air that reminded our bones of winter. We moved our camp kitchen out to a sunny spot for breakfast, and blew on steaming cups of coffee while the dogs shivered and looked miserable.

At first, we wanted to leave as soon as we got up – the better to get moving and dispel the morning chill. As often happens, a hot cup of coffee improved our outlook considerably, and the temperature soon rose to lift our spirits even more. We shed a layer of grimy camp-stained sweatshirts and draped them on bushes to dry any clinging moisture. Our goal at the beginning of the trip had been to confirm the phenomenon of the “cosmic motor” without the aid of herbs or drugs, and the stillness of this austere morning was the final proof. We kept saying “Shhh!” to each other and turning our heads to capture the nuanced song of creation being played all around us. Mist was rising from the surface of the lake, as the amber sunlight crept down from the tips of Altamira to the waterline. We exchanged glances of shared wonderment, and tried in vain to explain in words what we were experiencing with more than our five senses.

“It’s humming like an electric turbine,” I whispered.

“Yes, I feel a pulsing energy… and there’s also something beyond sound,” offered Suzanne.

“It’s the cosmic motor,” said Greg in his unpretentious, matter-of-fact voice, as if it was as normal as air. And it was. Every subtle shift of position or breath of wind brought to us a sublime new perception somewhere between hearing and knowing, as if we had been deaf all of our lives and were straining to hear far-off notes of Beethoven’s Pastorale for the first time. Gradually, as the power of the sun warmed the basin and another layer of clothes came off, the exquisite symphony of vibration faded into the rhythmic measures of another day.

There is always hesitation to leave Little Bear Lake. For me, there was a persistent feeling as if I was leaving something vital behind, like the keys to the car (and wouldn’t that have been a bitch!). I dawdled and dilly-dallied, putting off the painful separation for as long as possible. There really wasn’t much reason to pack carefully for the trip to the car, and there were fewer items. Nonetheless, I laid all my gear out on the rock in the manner of a mechanic preparing to assemble an engine. I took extra time to put the heavier items at the bottom of my pack so they wouldn’t propel me downhill and cause extra effort to regulate my pace. What I was really doing was delaying my departure, because in a way, I didn’t want to go back to the stifling, structured normalcy of relationships and responsibilities. This time the feeling was stronger than I ever remembered.

We left after a disappointing brunch of smashed Power bars, tortilla crumbs, clods of dried fruit, and more noodles. Being in civilization is hard work, but the food is much better! We were all sad to leave this unspeakably beautiful place, but we boosted our morale with enticing descriptions of what we would eat as soon as we got to a restaurant.

“A big, juicy cheeseburger and fries,” said Greg theatrically, “Or maybe two cheeseburgers.”

“I want a something fresh, like a salad,” gushed Suzanne, not knowing that the closest restaurant was a greasy spoon joint and not likely to have very fresh greens.

“I want something cold, like a milkshake,” I said with half-closed eyelids, “Or anything that doesn’t come in a wrapper.”

“Or that you have to add boiling water to,” agreed Suzanne.

“Like an ice-cold beer!!” shouted Greg, smashing a stick on a rock in a way that could have been a Neanderthal Budweiser commercial. The chipmunks that had been performing an advance inspection of our empty campsite fled in terror, tails held high, which old mountain men said was a sure sign a storm was coming.

There were indeed high clouds sliding in from the northwest, which is usually where the weather comes from around here. They had the scalloped look of cold air at the beginning of a colder front, and I hoped we wouldn’t get rained on after such a spectacular stretch of perfect days. It was getting unusually dark for midday, as the grey lid of the front slid over the sun slowly, like an enormous stadium roof closing. All packed up, and ambling down the trail to Wee Bear, there were no sounds from the birds or varmints in the forest. It seemed as though everything was halted in anticipation of something, the way an audience settles down when the lights are dimmed. We knew that the best view of the sky we’d have all day was from the Furniture of the Gods, so we took a slight detour up on the edge of the bluff to check the weather.

From this spectacular promontory that seemed to have been designed by a master architect, we could see 50 miles to the east, to the retreating remnants of the exquisite high-pressure system we had enjoyed for several days. I stood up on the stone “couch” for a better look. Mt. Shasta could be seen clearly in a warm, buttery light through an impressive crack in the distant gathering clouds, as if we were tiny insects climbing out from deep in the earth and peering out at the world for the first time. To the north over Sawtooth, the leading edge of the front had been sculpted into upside-down waves that veiled a threat of violence. Back over our shoulders to the west, the acute spire of Altamira looked like a reversed needle about to set down (up?) on an inverted vinyl phonograph record, where the sky was growing darkest.

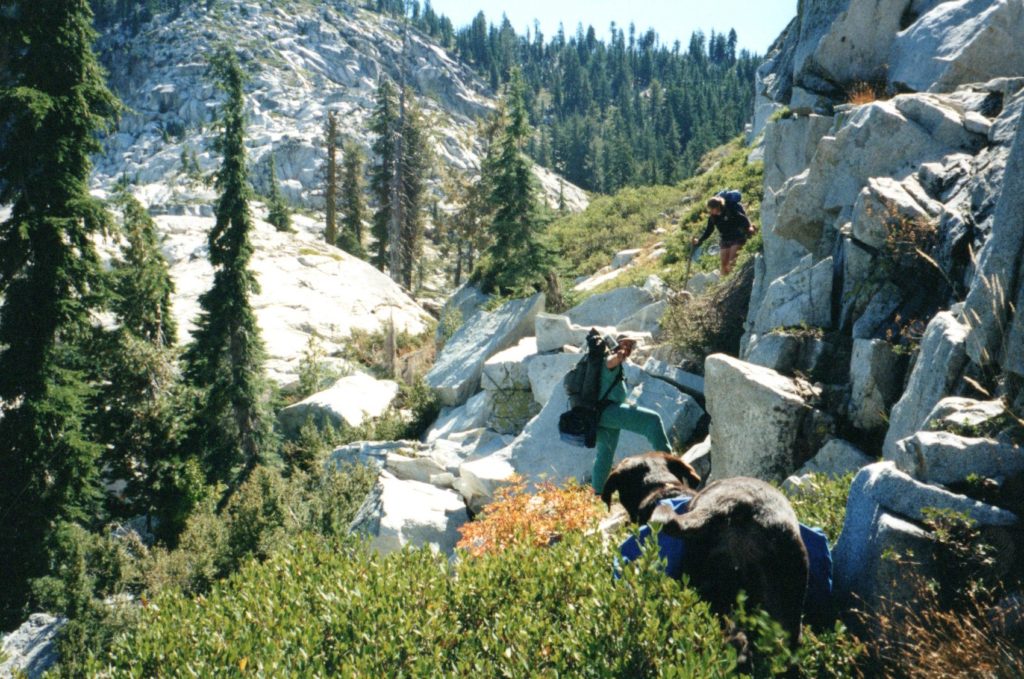

We discussed waiting out the storm in the cave, as I reminded them about my follies with Dave and Rob so many years before, trying to navigate across and down this huge, broken bulge of granite when it was wet. It was better to try and make as much progress as we could, in order to reach the trail as quickly as possible. My football buddies and I had foolishly tried to take a shortcut, angling 1,000 feet down the face of the bluff while it was turning into a natural water park. I had since learned that the fastest way down was to bisect the trail in the most direct line, no matter what the weather. We proceeded with alacrity, driven by the mounting electrical energy in the atmosphere. If we saw any lightning, we already agreed we would seek shelter, and not expose ourselves on the open granite. Visibility was excellent, with no sun glare, and we hustled back to the trail (without a rest stop) in about a half hour. So far, the storm had not broken loose, but the darker clouds had infiltrated the gray sky ponderously, as if searching for an opening to do their dirty work.

We might get wet, but it wasn’t water that concerned us the most. We didn’t know if the aluminum frames of our backpacks would actually attract lightning, but it was a mighty uneasy feeling to have the only metal for many miles strapped on our backs as we trekked across the shoulder of an exposed granite dome. We were much relieved to be already 500 feet down in the valley, and would drop another 1,000 feet in about an hour. We pressed on, after a short pack-off rest to adjust our loads for the hammering downhill march. Lightning did flash far behind us to the west as we entered the thick brush at the top of the trail, and we listened for the thunder but never heard any. The pounding of our boots and rolling rocks underfoot were the only sounds as we hurried. Sierra and Rogue were doing a great job staying out of everyone’s way — they could tell we were all headed home. At one point, Greg in the rear shouted, “Rock!” and I stepped to the side to let a melon-sized boulder roll by me where the trail was like a narrow creek bed. Suzanne was in the front and turned around with wide searchlight eyes, but well in time to let it bound harmlessly past her as if in slow-motion, where it came to rest with a resonating “Thud!” against a large fallen log.

“Oooh, got in on his hands!” Naturally, a baseball reference was the first comment from Greg.

“Broke his bat for sure,” I concurred.

“You guys are nuts,” said Suzanne, which was of course what a little sister should say in such a situation. She didn’t look too happy with how fast were trying to go. “Can we just slow it down a little and be careful? A broken leg would be worse than a little rain right now.”

She was right, but naturally we wouldn’t admit it. “I was going to ride that sucker down the trail like a trained bear in the circus,” Greg boasted.

“Well, we gave it a gravity boost for sure. It wouldn’t have made it all the way down there for another thousand years without us,” I pointed out.

“Why don’t you put it back then?” Suzanne was getting cross, and the smart-ass big brother team scored another run.

At the open place in the trail where an avalanche had swept through decades before, we looked back at the still-darkening sky, and decided it might not rain after all. “This could still be one of those dry lightning storms they get in the mountains,” I advised, “So let’s get under cover.” We turned our faces downhill, back down the trail, back to the car, and to our comparatively un-electric lives. The energy in the air was palpable, and it influenced our relentless pace unconsciously – even Suzanne, who was as much in a hurry as we were to avoid getting wet. Carrying a soaked backpack was no fun, and although we had brought plastic ponchos, we knew that wet camping gear would be a pestilence in the garage for many moons. We pressed on with haste, despite the fact that one misstep could drastically complicate our descent.

My feet began to bear the brunt of the maddening pace. Walking too fast heated them up, and they began to sweat. The sweat made my cheap tube socks slick and molded, like matching condoms. With each pounding step downward, my toes thrust deep into the fronts of my shoes like pistons, until they were mashed to a pulp and forming blisters on top of blisters. The abrasions erupted so fast from the lubricated friction that they dissolved and turned my socks pink with blood. (I discovered this much later, when trying to extract the remains of my toes from my hiking shoes.) This hyperbole is offered in sincere testament to the virtues of sweat-wicking socks, no matter what the cost or inconvenience to include in your gear.

“Hold on, guys, I have to rest.” My toes felt like they had lost their form, and were starting to disintegrate. The pain was indescribable; almost a religious experience. As a result of trying to favor my feet with each step, my thighs were burning and popping like campfire logs. My left knee was acting up, too, as if it didn’t want to be upstaged by the newcomers. Even my arms and hands were aching from overuse of my trusty walking stick. I realized I wasn’t young anymore, and that my physical body could no longer keep up with the enthusiasm of my mind. And so, I said “I have to rest” as a warning that this would be a longer than usual break. Besides, I had the keys to the car.

The electricity in the air had faded remarkably as we descended through the forested glades and rocky washes. No longer did it feel like all hell was about to break loose. It appeared as though the violence of thunderstorms was reserved for the higher altitudes that day. Birds were actually singing near where we rested for half an hour – in a spot I have dubbed “the hospital log.” I was laid out on a soft cedar deadfall, surrounded by an exquisite alpine forest, and picking at the remains of my toes. My leg muscles trembled uncontrollably, and quivered all the way down to my feet, where what was left of my toes twitched in spasms as I wrapped them in gauze. I had carried this particular roll of gauze up to the Bear Lakes and back at least half a dozen times, and I was determined to finally put it to good use. There was no satisfaction in the ministry, only numbness to pain like a Civil War nurse. Greg and Suzanne looked away uncomfortably, as if averting their eyes from a burn victim. I stuffed the bleeding stumps back into their hiking shoes and tottered to my feet.

It felt as if the bottoms of my leg bones were grinding into the gravel of the trail, as I gritted my teeth and did my best Clint Eastwood imitation: “Let’s go home.” The rest of the way back to the car was like a strange, incomplete memory of a distant nightmare. I remember nothing specific, only a downward spiral into new depths of pain.

“Your pain is the breaking of the shell

that encloses your understanding.

Even as the stone of the fruit must break,

that its heart may stand in the sun,

so you must know pain.

And could you keep your heart in wonder

at the daily miracles of your life,

your pain would not seem less wondrous than your joy.

And you would accept the seasons of your heart,

even as you always accepted the seasons

that pass over your fields.

And you would watch with serenity

through the winters of your grief.”

— Kahlil Gibran