“Our inward thoughts, do they ever show outwardly?

There may be a great fire in our soul, and no one comes to warm himself by it.

The passers-by just see a bit of smoke coming through the chimney and continue on their way.”

— Vincent Van Gogh

I awoke floating in a field of stars, my back pressed firmly on a rock; endlessly spinning in space. I restored my bearings gradually, and realized I was in my sleeping bag, ten yards from the fire, and camping at Big Bear Lake. The fire had burned all the way down, and the faint, ceramic tinkling of its embers was the only sound. Greg must have been too tired to snore. No wind stirred the water to lap on the shore. Tall, dark trees blocked out the stars at odd angles, creating a sense of imbalance. I could watch satellites disappear into the black velvet folds of their looming branches, and reappear on the other side. The textured masses of stars in my field of vision were three-dimensional, as they blinked on and off like unimaginably distant signal beacons. Incalculable masses of wayfaring photons, that had been travelling uninterrupted for millions of years, laid down to rest in my retinas. The warm night air smelled of earth, water, and evergreen.

I got up to go pee, and noticed that the warm, embracing air had a comforting effect, not unlike my sleeping bag. Dark-shadowed bushes and gray humps of boulders led me by memory to the latrine area well away from the creek. The sky to the north was glowing and backlighting the sharp edges of Sawtooth. Just as I began my nighttime business, the tip of a glowing moon breached the ridgeline, and the world changed. The gray boulders turned a ghostly white, and cast sharp, jet black shadows. The formerly shapeless blobs of dark bushes took on depth and pattern, and bristled in gunmetal green. The vertical bulk of tall trees, formerly invisible, thrust their vague, gray tops towards the stars, and their fat trunks crowded close to the campsite. I stayed to watch as the bright, gibbous face of Luna cleared the screening ridge, and shone her countenance on the glowing landscape. I stood there for a long time, transfixed by the optical illusion of the moon climbing into the indigo night sky, forgetting that I was the one who was actually moving – even though I was standing still. I was passing underneath Sister Moon at 64,000 miles per hour, pressed down on the surface of a giant, rotating ball of rock. I imagined I could feel the faint pull of Luna’s gravity and the centrifugal force lifting me to my toes. After a few minutes of reverie, I remembered I was still standing in the latrine area, and could find a much more pleasant viewing platform.

My legs protested feebly as I mounted the backbone of jumbled boulders that rose above the grasping bushes. The moon cast its radiance all over the basin, and illuminated the opposite shore of the lake. The peaks and ridges that encircled the water were not quite glowing, and not quite glistening. They had a subtle, luminous quality: like a phosphorescent jellyfish in murky depths, which I had to let float into the corners of my eyes to develop the best image. They flickered in and out of clarity, like an old-fashioned television with bad reception. The air itself was thick with interlaced bands of firefly photons arranging themselves in fleeting patterns. It was yet another magical moment in this intimate, amazing place. “How can this be real?” I wondered aloud, hearing the plaintive echoes of my previous backpacking trips. I basked in the endorphins of being awestruck for what felt like hours, but the moon had only risen a few degrees when the physical toll of trail fatigue once again smothered my senses. I gratefully groped my way back to my sleeping bag feeling fully alive, but tired… so tired…

The Last Day of Summer dawned still and spectacular. The morning air held memories of warm days to its bosom like a bouquet of wildflowers from a lost love. We were definitely experiencing an exceptional weather phenomenon known colloquially as “Indian Summer,” which is yet another reason I like to visit the Bear Lakes around the autumnal equinox. Slowly, like moths emerging from our cocoons, we shed the warmth of tangled sleeping bags and stretched our wings in the early sun. Once again, the lake’s surface was a shockingly reflective mirror. One had to strain to find even the slightest ripple on its surface. The steadfast sun illuminated the surrounding ridges in brilliant tones of gray and green, which appeared in perfect, upside-down reflections in the entire 58 acres of water.

I looked at my own reversed reflection, gnome-like and trail worn, with hair tousled in early morning tufts. Plucking out a few leaves and twigs, I ambled down to the shoreline, but decided to wash later, so as not to disturb the perfect surface. The entire lake lay flat as glass, with a slowly pulsating surface tension not unlike a diaphragm. I could hear noises of astonishment behind me, as my campmates discovered the water’s quicksilver display.

Suzanne waved off our attempts to guile her into cooking our breakfast. Having grown up with Chris and Greg, she was immune to guilt or subterfuge. Sierra and Rogue sneezed and snorted out the remnants of trail dust, and nosed halfheartedly through the bushes looking for the chipmunks that had stealthily invaded our campsite the night before. Small, exploratory nibble marks could be found on many objects, but they didn’t get at the food in its rodent-proof plastic containers. We had unpacked all our possessions the evening before, and arranged them on rocks as a flea market. It wasn’t too hard to repack everything, and it kept the unspeakable varmints from chewing holes in our expensive nylon backpacks to see what was inside.

We got a relatively early start on the last leg up to Little Bear Lake, and with our morning energy we spent some time route-finding through the worst jumbles of boulders and snarled brush. Most times in the past, I had taken a direct, perpendicular route to the crest of the enormous bulge of granite that fell away from the Cliffs of Dis Butte to the southeast of Big Bear Lake. It was much easier to zigzag up the blocks and ledges, as if climbing the side of the Great Pyramid. The goal (as usual) was to emerge high enough on the bluff to avoid the downward cracks that tumbled and widened towards the valley. Some years we fared better than others, and this time we found a natural shelf that might lead us all the way across the exposed, bare granite flank to Wee Bear, hidden in a cleft of trees to the south. We had full sun from the east, and the day promised to be warm, so we were grateful for the early start. What we found was by far the easiest way across the gnarled and twisted flank of Dis Butte. We made it to Wee Bear in less than a half hour from topping the crest. Greg had worked Suzanne into a frenzy of anticipation, and her reaction to the postcard-like beauty of the tiny lake was understandably hyperbolic.

“Oh my God, you guys!” She gestured most unnecessarily at the scenery. It was just as I had remembered it, like the face of a loved one to whom I had returned home. The gigantic, skeleton trees still towered in defiance of the elements on the east shore. To the south, where the snow melts into the inlet, lush green vegetation framed a perfect stand of healthy mountain hemlocks and Ponderosa pine. The intimate ledges and dainty specimens of fairytale trees formed a pleasing border to the west, that stepped up to the ridge. Everywhere the manzanita was dotted red, green, and yellow in a breathtaking, impressionistic autumn display; swirling with the energy and vigor of a Cezanne landscape. It was another perfect day, to be treasured and stored up as nourishment for dealing with the voracious demands of civilization.

I had asked Suzanne to tie Sierra and Rogue back a few yards so we could get pictures of an unmuddied lake. They whined and worried that they might be left there without getting to drink. Once released, they bounded into the water up to their bellies and lapped noisily, as I had seen every dog do that crossed the hot, white granite shoulder of Dis Butte to arrive in this spot. Their grateful antics muddled and rippled the shallow north shore, but we already had our unspoiled images in both mind and camera.

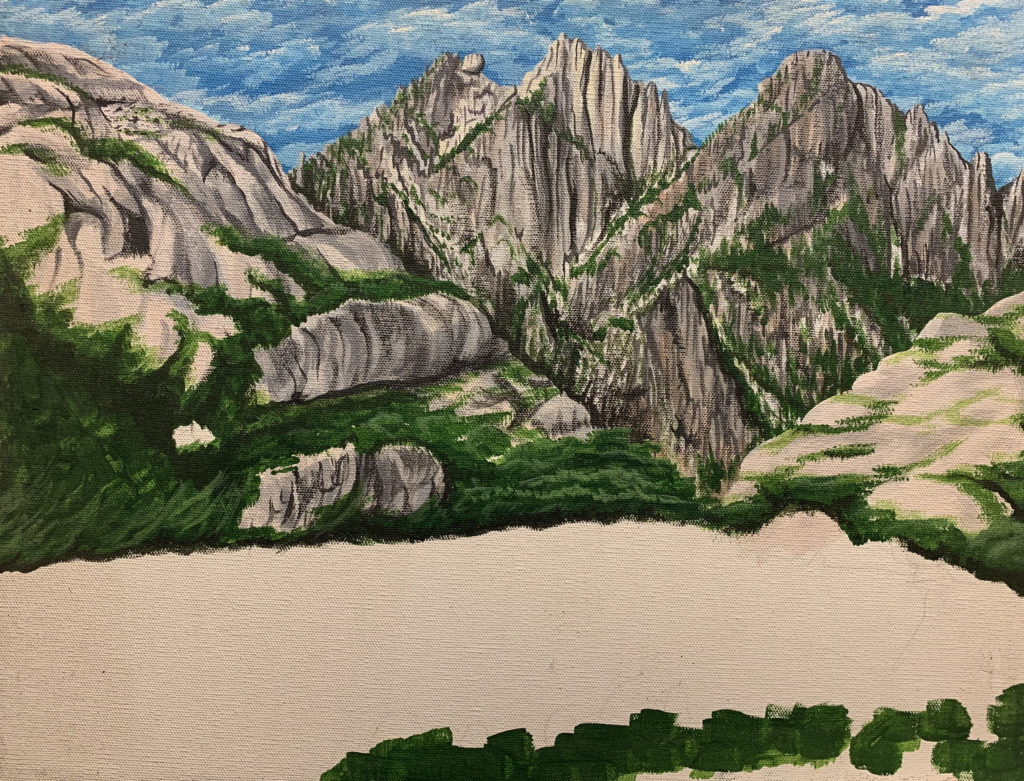

We ambled around the cute little east shore trail that danced among the brush and boulders, savoring the views from every angle. I was scouting for a good place to set up my easel, for I had packed acrylic paints, brushes, and canvas, in anticipation of an attempt to capture the beauty in an unprecedented way. This would be the first time I had ever painted (or even sketched) up at the Bear Lakes, and I wanted it to be memorable. I saw a likely spot as we crossed the inlet “creek,” and continued up the short walk to Little Bear Lake.

Amazingly, for such incredible weather there was nobody else camping in the entire basin. We had been the only ones at Big Bear Lake when we left, and we were the only ones here, too. This was the fabulous frosting on a delicious cake we had all to ourselves. We dropped our packs where we intended to sleep, and showed Suzanne the sights. The surface of Little Bear still had signs of beginning its day as glassy and still as Big Bear had been, but by now there were happy little ripples jitterbugging on the surface, with light sparkling as sequins on a stage performer’s costume. Nearly everything was remarkably clean, and perfectly landscaped by nature, with none of the unsightly blights of human habitation such as litter, erosion scars, or blackened fire pits. What had once been the largest Ponderosa pine at the lake had fallen across a large, flat area near the best campsite where we had stashed our packs. The trunk was about 3 feet in diameter; not too big compared to the giants in the valley below, but it had surely been a significant tree at this altitude.

I untied the large, framed canvas lashed to the outside of my pack, dug out my painting gear, and sauntered back down to Wee Bear, looking for the sticks that would form my easel. Mine was a reverent form of sauntering; careful not to step on any small plants. In fact, that word comes from the French Saint Tierre, which means “holy land.” When I had everything gathered at the spot I had chosen, I tied three 4-foot limbs at the skinny ends, and spread the thick ends into a tripod. Then I lashed the canvas on, using the loops I had stapled to its back at home in anticipation of this moment. I had come prepared for high winds, thinking of Van Gogh’s battles with the mistral in Arles, but this day was even more windless and perfect than yesterday, which I had thought to be impossible. This appreciation was most likely due to the fact that I was situated comfortably in the shade, gazing at stunning scenery, instead of lugging 45 pounds up a hot, sweaty trail. I settled myself on the little camp stool I had brought (1.75 lbs. and worth every ounce), and stared.

I became the Stare Master again.

Ever since I could remember, I had a remarkable talent for looking deeply into a landscape. When viewing nature, it often felt as if my eyes were organs of touch, caressing every nuance of the scene. I would get a sort of glow radiating from my medulla oblongata at the base of my skull, which seemed to project out of my eyes like two fantastic “tractor beams,” pulling in all the details of the scenery. This was at times a magnificent blessing, and at other times a curse. I had never developed as a painter due to this excess of perception, preferring to simplify my art into cartoonish images like animation backgrounds. As a boy, I was the only kid I knew who cared about the credits at the end of a cartoon. I had no mastery of the transformation of three-dimensional phenomena to a flat surface, unlike like some of the great artists I admired. My style developed in High School art class as I learned to use the tools of the trade, but my classically-minded art teacher would shake his head in exasperation every time he saw my work. Mr. Biasotti was a dear man, and a competent art teacher, but he could never figure me out. I earned an A+ every quarter due to my voluminous output and prodigious attention to detail; however, every effort I made outside of the curriculum he labeled “cartoonish,” and exhorted me to do better.

What could I say? I was a born cartoonist, and could not elevate myself above the artistic limitations of my avocation. I also couldn’t master the fine art of cartooning itself, but I was rather awkwardly prolific at times. I had a cartoon strip called “Living on the Fault Line” published in a local weekly paper for 10 years, and had developed quite an oeuvre. I started teaching cartooning at Fiona and Logan’s school, where I found a very eager audience of cherubic wannabes. My cartooning classes for kids were about as appealing to the young students as a workshop that teaches alcoholics how to mix drinks.

But today, I wanted to be a painter. It was still well before noon, and the light was ideal for my work. There was a rare clarity of atmosphere due to the low humidity, and an even rarer lack of fires in the area. I looked at the incredible scene before me, and gulped at the challenge. It’s a simple matter to paint what you see. After all, it’s right there in front of you – all that’s left to do is to reproduce its appearance on canvas. Color, brush, and hand merge as one mind, and the details are transcribed. What is so vexing is how very much one can see!

If one can paint, one must paint! If one plays an instrument, one must play! If one is able to write, one must write! The expression and preservation of any creative individual’s thoughts is a vital contribution to the unfolding of the universe. From the noblest thoughts of saints, to the ugliest notions ever recorded, all are a genealogy of our evolution as a species. How could it be otherwise? How should humans learn the breadth of what is right and wrong, what is good for the universe and what is not, except by a review of recorded art and history? Express yourself! Sing your song to the world! Dance like your life depends on it, because it does!

And yet, the bane of my muse persisted. I could see everything at once, which greatly hindered my ability to replicate it one brushstroke at a time on the canvas. I attempted a wash for the sky, which didn’t work well with acrylics on canvas. The problem was, there were no clouds to add depth or texture to the vast azure firmament. I made some up, they didn’t look right, and I spent a long time just trying to make something convincing out of the falsehood I had created. With ambitious folly, I tried to capture the entirety of the astonishing ridgeline of Sawtooth, and the myriad cracks and crevices on the stony, flat planes of its teeth. There were probably over a hundred distinctly recognizable colors making up what an unseeing person would call “gray.” I tried to reproduce these on the canvas to no avail, making a mess of things. I vacillated between cartoonish representation, and the fine control of photographic realism, and the result was a mess. I stopped deliberately after a few hours, thinking my work might have more aesthetic value if it were left unfinished, like Whistler’s portraits.

At that moment, I realized that I was irritated instead of being satisfied, and not grooving with nature like I had anticipated, and I examined this feeling to soothe it at the source. The seedy feeling of “not being good enough” had sprouted up, and was developing thorns, but I was not about to let it ruin my garden. I recognized with compassion that these weeds of inadequacy germinated as a boy, from hopelessly wanting to please my father. My feelings of inferiority grew larger and pricklier from never winning his approval or affection. I intended to pull them up by the roots and turn them to compost, but somehow could never bring myself to kill them. They were my own creations after all, and in some complex way, were also an emotional tie to my father. And so, I trimmed them nicely as usual, and knew they would grow back soon. I immediately sensed a release, as if everything was ok… including me.

By this time, my mind was exhausted and completely drained of creative urges, with the torpor of a burnt-out artist at a midnight café, intoxicated by absinthe. The tension of having to “see” the connections between my subject and my canvas had taken everything I had, and still it was not enough. The mind plays a very important role in art, and mine had left me short of the mark once again. My mind was a much better interior decorator than a painter!

As a mental exercise, think of what goes on in the mind when observing a painting in a museum. First there is the immediate emotional response, such as “Oh, that’s nice,” or “Yuck.” Then, as one inspects the details of the composition, the play of colors and design elements combine to produce a deeper, more fundamental response. One may be often moved to insight: “I wonder what the artist was thinking of?” This seldom rises to the level of intellectual affinity that comes from intuitively comprehending the answer to that question through observation of paint applied to a canvas. Good artists can stimulate this insight more often than others. Very great artists such as Van Gogh or Cezanne may transport a perceptive art lover to an entirely different level, where the synergy of sight and creative intent produces a third element of experience other than painting and painter – now there is also an Observer. Thus, the enlightened viewer participates in the act of creation all over again, and the mind of the artist is immortalized.

I looked out one last time at the scene I had tried in vain to reproduce on canvas. The viewer cannot be separated from the view; just as the experiment cannot be apart from the observer. The spectacle is too deeply rooted in the spectator. The supreme genius would be to convey the essence of this beauty in such a way that all creation could feel its benevolence. What was in the mind of God when she created such spectacular scenery?

The shadows had lain down softly to a demure angle, and the clear light of midday dwindled in the spent afternoon. Sawtooth and Wee Bear sat immutable in their grandeur, wholly unimpressed by my puny attempts to reach immortality. I disassembled my au natural easel, and deliberately put the branches back where I had found them. As if the forest might forget that I had tried to take away a part of it. Who was I to try and capture the intrigue of nature and put it in a cage like a rare bird? The scene was indelibly preserved in my mind and memory, where the effect was forever pure and unadulterated by limitations. The sun was nearly setting to the west when I resigned myself to settle for a third-rate, unfinished painting and a first-rate headache, and trudged up the little trail back to camp, trying to hide my erstwhile masterpiece. Suzanne saw me coming and waved.

“What’s that?” Greg asked from where he was picking his feet. “Bam!” The door slammed shut on my contemplation of ultimate beauty.

“Oh nothing,” I said lightly, carrying the canvas so only the thin edge faced them.

“You did a painting?” Suzanne exclaimed, “Let me see!” I held it out casually, like displaying a minor scrape on the knee that didn’t hurt at all.

“It looks flat,” Greg offered with erudite tact.

“No, it’s just that all the parts are trying to exist at once,” I shrugged dismissively, with the vague weariness that comes from too much awareness.

Suzanne scrutinized me the way a nurse might assess a patient. “You look like you need some coffee!”

“At some point the world’s beauty becomes enough.

You don’t need to photograph, paint, or even remember it. It is enough.”

— Toni Morrisson