Our last morning dawned crisp and bright like an autumn apple, but we were in no hurry to leave. Cautious noses peeped out from warm sleeping bags and withdrew again hastily, until the morning chill had been eased by the appearance of the largest fire in the solar system. We arose puff-eyed, in scratching, slothful disarray, to find that the blackened fire ring which had once staged the glory of our Man Fire was now a garden of fine white ash. It still radiated significant heat however, and when I poured a cup of water into the center it hissed and blew out a vent of steam from deep under the blanket of ashes. We took turns bringing water from the lake to drown the protesting embers, and they eventually died a noisy, gray death. Then we used a plastic tarp to shovel out and transport the charcoal muck into our prepared hole, along with many of the blackened stones. More water was poured until the ground was safely cooled. We had planned all along to leave as little trace as possible. Eventually both holes were leveled off, covered with topsoil, and sprinkled with the fine white crumbled granite that passed for sand around the lake shore. The end result harmonized perfectly with the scene, nutrients were delivered to the developing soil, and the campsite was restored to its idyllic wildness.

Although we were exhausted from the vigorous campaign of manly chores we had inflicted on the landscape, we were too proud to show our fatigue, and guzzled steaming mugs of wicked, black coffee that could float a chunk of granite. Today we would conquer one last adventure that remained as unfinished business from previous excursions. We were determined to find a shorter route back down the slanting crevices in the massive mountain of rock that we had scrambled over on our way up to Little Bear Lake. Formerly, the route of descent had always been to retrace the steps of ascent, owing to the lateral flow of the cracks and ledges that stepped down northward across the mountainside. It had always seemed easier to stay above the worst crevices, where one could clearly see the path ahead and down. Perhaps emboldened by the crucible of our Man Fire the night before, we scoffed at what seemed “easy,” and trampled prudence with the restless hooves of our impatience.

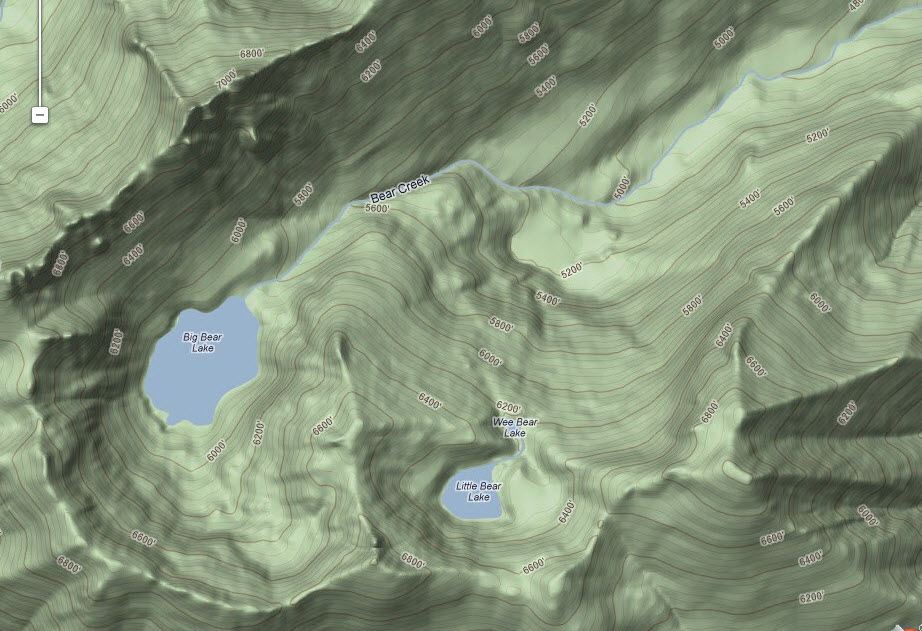

From the cleft in the rocks at the north end of Wee Bear, a wide, natural causeway angled downward in a deceptively straight line, until it bisected the trail on the other side of the broad, glacial valley in the area of the largest avalanche-strewn boulders. This inviting crack we could see was choked with small trees and tangled brush, owing to the rich overflow when Wee Bear spilled over from snowmelt in the early summer. We remembered seeing this landmark on our way up the trail, appearing to offer an easy way up… if we could only get to it. This “if only” might have been a warning signal to more receptive minds than ours. Still, our audacity was tempered by a healthy aversion to bushwhacking, and we reasoned that we could descend this brushy path on the bordering shoulders of granite, and save a lot of time on the way back to the car. Another, equally compelling motive was to find an easier way up to our stomping grounds for the next trip. This is always the way of the explorer: to find the Northwest Passage, or the shortest trade route to the riches of the Orient. Man is always trying to do things better, faster, more efficiently. Whatever peace may be lost by not taking the easiest path was not a consideration. For our intrepid band of adventurers, we just wanted to get a burger and a shower as quickly as possible. Was that too much to ask? Well, if we had bothered asking, and if we had been able to hear over the din of our own blustering, we would have surely heard the gods laughing in our faces. As I had learned painfully so many years before with Rob and Dave: short cuts make long delays. Another truth that dogs the footsteps of our species through time is the fact that repetition of the same mistakes is often required before we learn… if we ever do.

The descent on the shoulders of our grand, green promenade went easily at first, and we dropped several hundred feet with no problems at all. We could see the trail clearly across the dark line that Bear Creek had made as it tumbled down towards the North Fork of the Trinity River. The river was barely 3 miles to the east as the crow flies. If I had seen a crow flying that day, I would have cursed it in its own language. The brush-choked boulevard petered out halfway down the mountainside, and broke up into a labyrinth of blind alleys and convoluted granite ramps that dodged the jagged boulders that had tumbled down amidst the thicker brush like huge broken teeth. The scraggly manzanita grew lush and thick in the clefts between these toothy fragments, and we soon tried gaining back some of the altitude we had happily given away before, to try and get above the inhospitable bush garden. We paid penalties with time, sweat, and scratched shins, to regain orientation with the trail… which seemed farther away than we had hoped at this point.

“If we’d taken the usual route, we’d be crossing the creek back at the pools right about now,” I said unnecessarily, after about an hour had passed. This was met with disdainful snarls and growls of derision for my navigational hindsight.

“We’ll meet the trail about a half hour lower, right over there.” Greg pointed to a section of trail that was partially obscured by a line of thick green growth. The terrain had flattened out a little, offering more chances for the vigorous manzanita to grow tall and impassable. We were well upstream from where Rob, Dave, and I had struggled mightily through the underbrush in our reckless tussle with disaster. At least it wasn’t raining, and the creek would be quite low this late in the season.

After scrambling – or more aptly, swimming – up and over one brush-tangled cluster of boulders after another, we finally leveled out some more, and it seemed as if we could make our way over to the trail, still mocking us from a few hundred years away. The stern spires of Sawtooth were all set on edge at this close angle, and loomed discouragingly. When we reached the creek, we could see clearly why this route was not ideal. The tiny little stream had created its own modest Grand Canyon of sharp-edged rim rock, great broken blocks of gray-green granite, and crumbling vertical cracks. This was achieved not from erosion, but from frozen water cracking the solid rock. This would have been quite an obstacle if there had been any water to speak of, but far below in the dark depths and clefts in the granite, only a happy burbling sound was heard where no water could be seen. Downstream from where we stood, the snarls of alder and mountain hemlock looked very uninviting, so again we regained altitude until we found a better spot to cross. Shin-barked, grumpy, and peeved with shortcuts, we finally bisected the trail about two and a half hours after we had left the lake.

“We could be almost to the car by now,” I said just to piss everybody off. It worked.

Once again, and because of our audacity and disdain for common sense, the journey down the trail lost all sense of sightseeing or adventure. It became a mindless plodding to reach the car as soon as possible, and end the ordeal we had created for ourselves with our stubbornness. Each foot fell into place while the eye picked out a landing place for the other foot, and so on, until the few miles were devoured and the welcome bulk of the Battlestar loomed between the last few pines. Six hours after we left the lake, we dug the cold drinks from where we had cached them in the creek, and glared at each other slack-jawed, like stunned earthquake survivors.

“I bet that stupid water beat us down the trail,” Chris said in the direction of the creek; to no one in particular, and not one adventurer would acknowledge the humiliating defeat. We were just happy to get the downward-dragging weight off our backs, and we piled dusty gear and sweaty bodies into the cargo holds any way they fit, and bumped back down the dusty road to the main highway. Our energy and boastful bravado were revived shortly after demolishing bushels of cheeseburgers, and we traded insults and reminisced on our exploits all the way back to the Bay Area. Orienteering gaffes were soon forgotten, and the epic conquest of wilderness was left to be written in the history books, which we knew would cast a favorable light on our accomplishments.

The faithful Battlestar nearly made it all the way home before it died. It blew a rod out the top of its manifold at the base of the dirt road to my house, and I had to shoulder that awful load one last time. As I trudged up the final two hundred yards to the Rusty Bucket Ranch, I reflected that the car’s timing had been nearly perfect, and it died a noble death, along with our sense of youthful innocence. After conquering the wilderness, is it any easier to tame the wild places in the soul? Or are we forever searching for shortcuts to enlightenment, avoiding the productive pathways of discipline, and making for long, painful delays in our development as human beings? There may be great windows in our souls, but we keep the curtains shut tight and argue about the view.

“We need the tonic of wildness…At the same time that we are earnest to explore and learn all things, we require that all things be mysterious and unexplorable, that land and sea be indefinitely wild, unsurveyed and unfathomed by us because unfathomable. We can never have enough of nature.”

— Henry David Thoreau