Marty couldn’t stop creating, and wrote more dismal poetry (with one piece called The Shadow of Love) to repudiate Michelle for not being ready to love him. He also composed an epic tome modeled after Al Stewart’s Love Chronicles, in which he detailed his romantic misadventures from an early age to the present, ending on a falsely positive note because he didn’t want anyone to read his true thoughts. Marty had become a charter member of the legion of emotionally walking wounded. Life at school was a cheap imitation of reality. Everybody acted so phony; they didn’t know a damn thing about the real world. He had no kindred spirits with whom he could share his feelings, other than Chas, and he was too cynical and judgmental to understand the depth and tenderness of Marty’s sorrow. His left leg was nearly a hundred percent healed, with no trace of limp remaining, but now his heart was crippled. The ups and downs of his pseudo-relationship with Michelle had worn his nerves to a frazzle. He experienced an ever-increasing intensity of mood swings: from the dizzying heights of hope and exhilaration, to the darkest pits of despair. Shut inside his room most of the time, he listened to tragic songs over and over again… like this one from April Wine:

“It’s coming right down on top of me,

And getting so I can’t hardly breathe.

It’s coming right down on top of me,

Just won’t let me be…”

Regardless of Marty’s mental and emotional state, as the resident crazy artist of the school “village,” he was expected to continue writing and drawing cartoons for the Jolly Roger, and so he did. To challenge the readership (and perhaps send out a distress signal), he laid his soul bare in an emotionally charged column, but not a single person commented on what seemed to him to be an obvious allegory about his utterly disconsolate emotional state. The column was published with a prominent headline on the editorial page where most students and nearly all the teachers were sure to read it. This is what he wrote… you can judge for yourself:

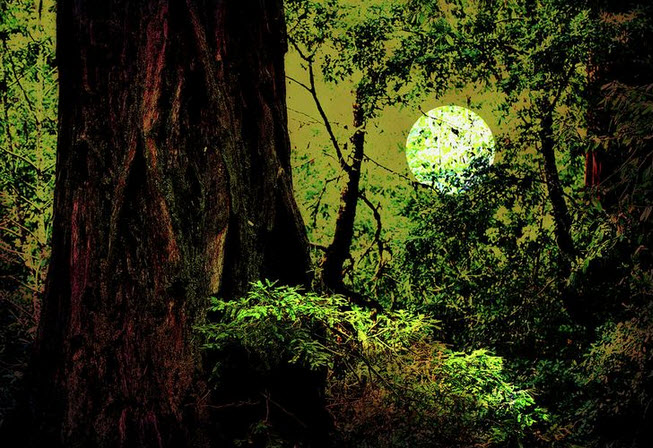

The Fragile Life of Dreams

Once there was a man who never did anything right. However, that was until he bought the tree. He planted the young sapling in his front yard on a delicious spring day, and stood back and looked with pride at his new project. Deep inside, he desperately hoped he would not fail again.

Every successive day saw the man out in his yard, faithfully caring for his young tree. He would prune, fertilize, vitaminize, and even talk to his tree for endless hours. Night would find the man peering fretfully out his front window every half hour, making sure that his tree was all right. In effect, the man watered his tree with his very life’s blood.

Fortunately, his efforts did not go unrewarded. In time, the tree thrived as none else did on his block. It grew with amazing speed, and was a favorite of the orioles and sparrows that the man loved to watch so much. He could spend the whole afternoon sitting under the young branches reading to himself, and sometimes out loud. His whole waking day revolved around his obsession for the tree: planning, working, giving, and all he asked in return was that his project survived.

And it did. The seasons turned into years, and the years into decades, watching the tree grow with such rapidity and vigor that it was the envy of the neighborhood, yes, even the whole town. Its caretaker, now an old man with the satisfaction of having done something right for a change, still treated his tree with the same tenderness and devotion as before. The neighbors swore he was crazy, and kept their children away from his yard, even crossing over to the other side of the street as they strolled by.

This could not bother the man, even when he felt lonely. He would just sit out in the yard under his tree and read poetry, sometimes out loud, and the birds would gather in the branches to sing and flit about, seeming to listen intently to his every word.

As all good things must come to an end, all great things shall meet with disaster. A particularly violent and stormy night moved the man to sit intuitively at his window, watching his tree flail in the wind through the sheets of rain that smashed on the glass. He was enormously worried, as one might expect, and he was already thinking of ways to repair his tree, his life, when calamity struck.

A vicious, seething bolt of lightning tore through the air outside the house, ripping his tree into shreds. The crown of leaves burst into flames, and the stricken man watched in horror as his life burned to the ground. He dashed out of the house, screaming into the night, and the night screamed back with lashes of rain and roaring winds that pushed him around like a leaf. He staggered back into his house, sobbing hysterically, and passed out on the living room carpet.

Understandably, he never recovered from the shock. He sat inside his house with the drapes closed, never going out, never eating. There began a noticeable physical change in the man. He developed an insatiable thirst, which showering three times daily couldn’t even satisfy. His hair turned coarse, and rustled when it was dry, and his skin hardened, with rough, scaly patches.

The weeks passed, and the neighbors began to worry, for they noticed he hadn’t left the house since the storm. They called the police, who in turn investigated, entering the house one delicious spring day. The officers were bewildered to discover a lifeless, twisted tree still gripping the living room carpet, where it looked as if it had been growing for a long time. There was no trace of the man at all, and the official report said, “Suicide – no body found.”

Of course, there were the usual circulating rumors regarding the nature of his death. The neighbors swore he died of a broken heart, but in reality, he was killed by Dutch elm disease.