Mike was already 18, and seriously considered dropping out of high school. He was deeply affected by the horror of his return to Drake, and didn’t want any babes staring at him, who used to know him as “a fox.” Marty entreated him to stick it out somehow and get his degree, which would at least give him options, so he didn’t wind up inhabiting the Slodge the rest of his life.

Marge called Mr. McIntosh, to whom she referred as “your nice principal,” and arranged to have Mike transferred to another school. Even though the kind administrator wasn’t actually the principal, he knew just the right place for Marty’s brother from another mother: a small, special needs school called Mewah that helped kids get over the hump and graduate. Marty didn’t see much of Mike after that, but when asked about his new school, he said it was “okay,” which meant he hated it. Still, he stuck it out, shrugging poignantly, “It’s easier with kids who don’t know me.”

Annie was extremely fretful without Mike at the same school, because that meant he might find another girl. She was so insanely jealous that she cut her own classes so she could stalk him at his new campus, until he found out about her obsession and freaked out. He blew up at her, yelling, “Leave me alone!” She was rightfully hurt by his reaction – she’d stuck by him, rarely leaving his side after the accident, and was figuratively caught in the grip of seven demons, with fear that he might leave her. The sudden separation was hard on both of them, after they’d been through so much together. To make it worse, Mike told her they should stop seeing each other for a while. Each day at Drake, Marty had to witness the miserable mélange of Annie’s face, which was often blotchy and red from crying while being comforted by her friends. Her court glared unfairly at Marty, because they thought he was guilty by association, so he limped harder and fumbled with his crutches for sympathy. Later at home, Mike would be nearly comatose with guilt and concern, grilling him if Annie did this, or asked him that… it was both onerous and pitiful at the same time. At school, Annie checked in with Marty several times a day, because he was like her brother and she trusted him. He told her the truth: Mike wasn’t seeing anyone at his new school and just needed some space because of what happened to him – it had nothing to do with her. He told her the best way to support her man was to respect his need to be alone sometimes, and not take it personally. She didn’t like hearing that but some of the logic seeped through, and she calmed down a little, until she only asked about Mike once or twice a day.

Meanwhile, Marty was speculating on his own romantic aspirations, but now he had two handicaps: his gimpy leg, and the drama of Mike & Annie following him the way rumor shadows a celebrity. Besides, it drained his own spiritual batteries to always be the transformer for their electric emotions. They needed to talk to each other or somehow work it out on their own. Marty needed to save his strength, in order to compete for the hand of the fairest maiden in the kingdom! But who am I kidding, he chastised himself: what realistic chance do I have with lovely Michelle anyway? She lives in a perfect house in a perfect neighborhood, and I live in a shack in the woods. Her family is super rich, and mine is poor. She’s remarkably beautiful, and I’m pockmarked with acne. She will be going to UCLA, while I’ll be lucky to take art classes at College of Marin. He wondered, did I miss anything? He wanted to find all his toxic fears and expose them in the light, because “Ya can’t fix what ya can’t see,” as Otter used to say.

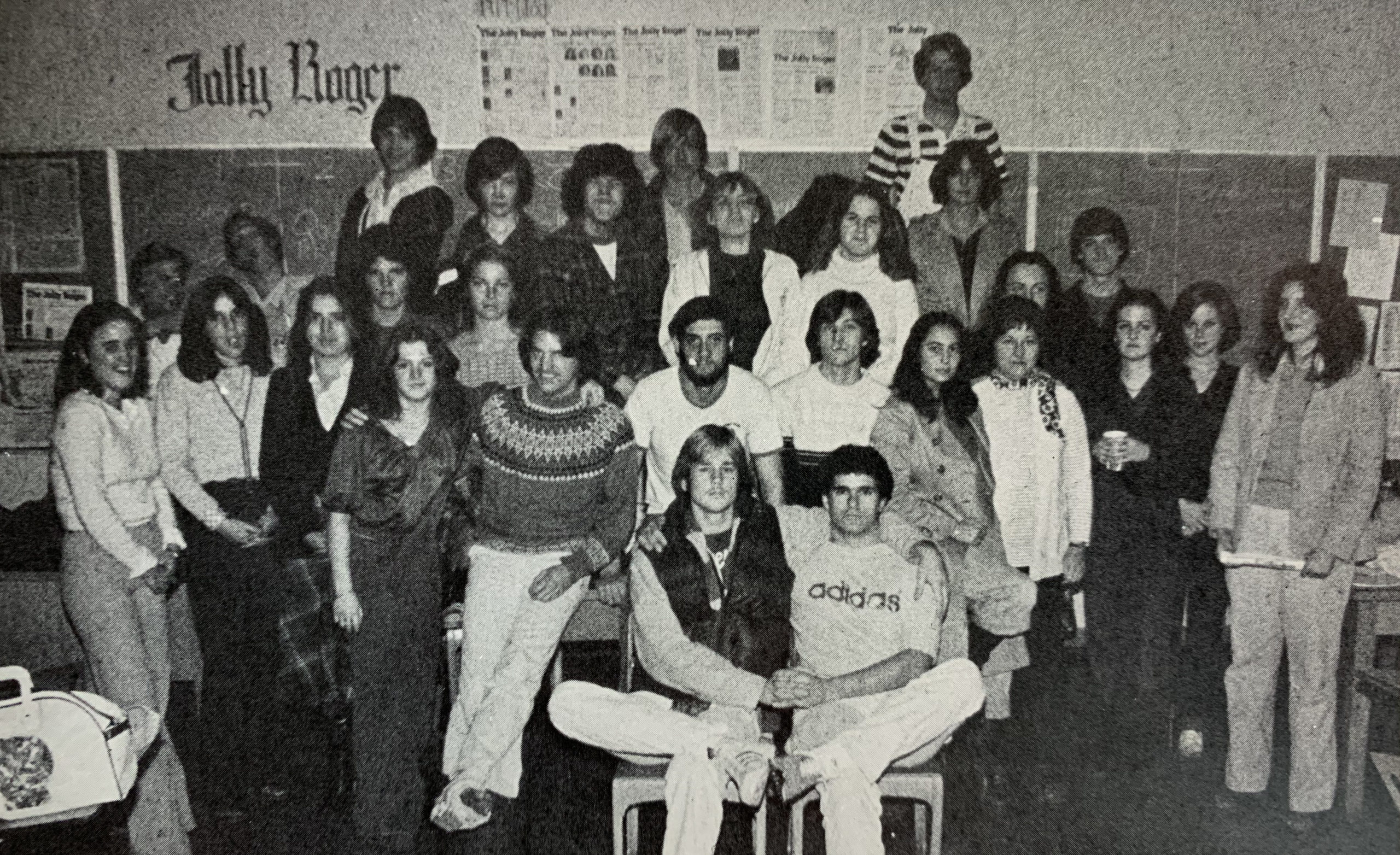

Michelle remained pleasant but reserved in journalism, while Marty cavorted with the rest of the Bohemian pseudo-intellectuals on staff, like Will, Nick, and Bruce. They were all witty writers with a strong sardonic streak, and far too many ideas to fit into one issue. They had a little competition going to see who could get the juiciest innuendo past the sharp eyes of Mrs. Hess. Their favorite pastime was mocking Mark, whom they dubbed “the fluffiest girl alive,” because he worked so hard to get his hair feathered on the edges in the current style favored among puff balls and poofters everywhere. He was the tall, handsome basketball star, and they were short and cynical. Mark was actually a decent guy, and took all the ribbing good-naturedly, which infuriated them even more.

Marty’s birthday finally came, and he was literally itching to get the cast off his leg. He was 18 now, and a legal adult (as opposed to illegal?), so he could make his own decisions in life. Starting with: if he didn’t want to come to school, all he had to do was write himself a note. Mr. McIntosh was in charge of attendance and called Marty into his office about his first note, which was written to excuse his absence on his actual birthday. “I wanted to make sure you didn’t forge this,” he said with a grave expression, and Marty wondered if he’d been smoking confiscated weed, until he laughed too loudly and said, “Gotcha! You might be able to excuse yourself now, but you’ll still have to meet minimum attendance requirements to graduate.” Marty asked him frankly how many times he could be absent the rest of the year, and instead of answering, he asked him how his family was doing.

“Um, we’re okay, I guess.” Marty was taken aback, because it was the first time any adult who knew about Mike’s accident acknowledged the possibility that the family of the victim might be affected, too. Mr. McIntosh already knew how Mike was doing, and said he was in contact with Mewah administration to help encourage him to finish school. But he was also concerned about Marty, and Susie too, who had just entered Drake as a freshman.

“Well, if you need anything let me know.” He looked like he wanted to say more, but his bureaucratic sense of protocol wouldn’t let him cross a boundary. “I’m here for you.” Marty left thinking, yeah right, you’ve been hassling me since I came to this school… but somehow that felt shallow.

Coincidentally, Michelle’s birthday was the day after Marty’s, and he used the opportunity to try and reengage her in meaningful conversation. “I was born in Milwaukee,” he said by way of comparison, milking the coincidence that their birthdays were on consecutive days (albeit a year apart), “How about you?”

“Here at Marin General,” she said brightly. “How’s your ankle? Shouldn’t you be getting the cast off soon?”

Marty took her interest in his health as a very positive sign, and reminded himself to breathe and focus on her eyes. He firmly… or rather pointedly… avoided looking at her breasts, which were attractively covered by a fuzzy sweater. “Yes, I’m getting off – I mean, it’s coming off next week.” He blushed at his Freudian slip. “Hey, maybe we can do a feature together,” he said in spontaneous inspiration, “You do the story and I’ll make an illustration.”

She responded with enthusiasm, “That’s a great idea! Let me talk to Mrs. Hess about it,” and then she beamed at Marty with her life-giving, ray-of-sunshine smile that melted all his past disappointments and heartbreaks like snow in the spring. From her point of view, she was just being friendly. From his, it was a glorious resurrection. All day he saw that radiant smile, and her sparkling eyes connecting with his, sharing a happy moment together. He felt so good that he told Mike about his infatuation with the legendary Michelle.

“Wow, she’s pretty fine, man.” He looked at his little brother with new respect. “You have good taste. Does she like you?”

Marty told her what she’d said about the Homecoming Dance, and he whistled. “Maybe ya got something there, Stripes.” That was his nickname for Marty, but he wouldn’t explain it. “Okay, this is what ya gotta do. She’s a high class babe, right? So ya gotta treat her right. Ask her out to a play, a fancy restaurant, that sort of thing.” He was on to something. “Just be yourself. You’re a total gentleman. Chicks like that will love you when they get to know you.” Marty was flattered, and thanked him after a moment of stunned silence. Then Mike passed him the bong he’d been preparing, and it was time once more to escape reality – except now Marty wasn’t so sure he wanted to get away.

It was Homecoming Week, and although Michelle wasn’t chosen as one of the Princesses, Marty admired her all the more for it. He fantasized that she didn’t want to get caught up in that sham, despite being the prettiest girl in school, because that’s how he would have felt if he was her. They had ridiculous events planned all week, like Pajama Day (with teddy bears), Twin Day, and powder-puff football. As it turned out, Marty was glad he didn’t express his acrid opinions out loud, because Michelle was on the flag football team, and she was positively awe-inspiring in shorts! Her legs were long and shapely, but strong and toned. She had what people called a “dancer’s body,” with graceful lines, a long neck, and a gorgeous backside. Of all the actresses Marty considered, she resembled Grace Kelly the most. The Homecoming Dance came and went, and it was couples-only. He thought it was discriminatory to exclude those who wanted to lean against the wall, miserably waiting for someone to ask them to dance. When he thought about it, he was offended that a public school was so exclusive as to enforce a policy that only “couples” could participate in such an iconic school spirit activity. To the best of his knowledge, Michelle did not attend, and he breathed a sigh of relief. Maybe she had no other love interests!

Meanwhile, Marty had been enjoying America’s latest album, Silent Letter, since it came out during the summer. It was their first LP in a while, but one of the founding trio had left the band, so he didn’t know what to expect. It was quite a break from their previous style, and they nailed it. There were several songs on the album that spoke to him, including a sappy love song that would be appropriate to play at a wedding, called All My Life. Marty was having trouble just getting a date, so thoughts of weddings were far from his mind. Still, he was a sentimental young fool, and figured chicks dug that kind of stuff. Although he was young, he knew he wanted to find someone with whom he could share a lasting relationship – unlike the people he had observed in his lifetime. The lyrics in the song touched a very deep nerve, indeed.