There were several football practices scheduled before the school year began, and Marty always found a way to get over the hill one way or another. One time, he rode his bike the entire eight miles, and that was a big mistake. It had no gears to make the hills easier, so he arrived worn out, and was uncharacteristically sluggish during practice. Coach Connor (the kids just called him ‘Coach’) made him a halfback, joking, “That’s as much ‘back’ as you got.” Marty rewarded his gridiron acumen by beating the defense to “the corner” time and again, which caused Coach and his assistant to smile with sly speculation. They gleefully referred to him as their “secret weapon,” and scribbled on their clipboards.

Marty called his dad to tell him that he’d made the team. For once, G.O.D. was genuinely surprised, which somehow translated as an affront to his omniscience. He mumbled vague platitudes about coming to see his first game, which would have been an unprecedented level of involvement in his son’s sporting activities. He never attended any Little League games, or played catch like other dads Marty knew. The sensitive lad was always trying to reach over the wall that G.O.D. maintained between them, and he privately lamented that his advances were met with ambiguity, at best. Like most boys, Marty had dreams of someday impressing his father, so that he might acknowledge him as a man.

In the final days of summer, over Labor Day weekend, Julie wrecked her V.W. Unfortunately, her siblings were passengers at the time, and it happened so suddenly they didn’t even have time to be scared. They were coming home from a friend’s house in San Anselmo, and Julie rear-ended the car in front of her at a stoplight. Marty was riding in the hatchback; without a seat belt. He was hurled forward into the front seat, where Julie and Susie were shrieking with alarm. Fortunately, none of them was hurt badly, but Marty banged his knee pretty hard on something, and had to miss a couple of practices. Now that his first game – and the beginning of high school – were just a few days away, it sucked to be limping around like a cripple!

Julie was distraught over the loss of her wheels, and realized she would have to get a ride from her mom, which was even more embarrassing than having to tell her auto shop teacher she totaled her senior project. Not the best start to her final year in high school.

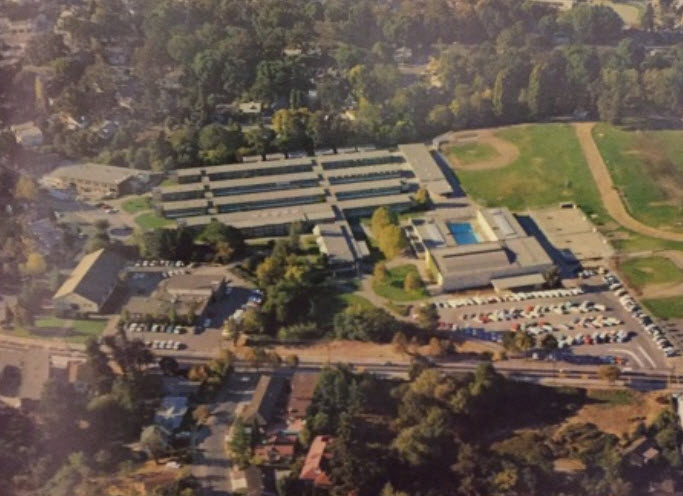

Susie would be entering the 6th grade at Lagunitas School, so all of them would have to cram into the stinky front cab of the Toyota… because the back of the truck smelled far worse, from hauling garbage cans to the dump. When the big day finally came, Marty still had a slight limp, but he remained hopeful he’d get to play in his team’s first game the following weekend. Marge dropped Susie off and continued over the hill through Fairfax. Julie wanted to be let out at the back of the school so her friends wouldn’t see her getting a ride from her mommy. She and Marty walked the final two blocks to Sir Francis Drake High School, towards the back gate on Fern Lane.

Right away, Marty saw a skinny kid waving him over to the fence. The boy was dressed in a ski cap and thrift store clothes that didn’t match, and Marty hoped that was the current fashion because it would mean he had a perfect wardrobe! He noticed other kids carried their stuff in small backpacks, but all he had was an old briefcase he found under the Goodwill truck. The skinny dude looked even younger than him, and was unusually friendly, but his ulterior motive became obvious as Marty approached. “Hey, dude, can I bum a smoke off ya?”

“I don’t smoke cigarettes,” Marty answered with a neighborly shrug, which was true.

“Dude, don’t be tight! You reek of cigarettes, okay?” The ski cap waved him off and selected another potential philanthropist. Thanks Mom, Marty worried wryly, and sniffed the ends of his hair. This should do wonders for my social life.

The street scene just off campus was new and exciting, with groups of students greeting each other, parking their cars, and ravaging their lungs in a haze of tobacco. Smoking wasn’t allowed on school grounds, so the “safe zone” between homes and the school was heavily polluted. Julie ditched her little brother as soon as she could, leaving Marty to survive his initiation alone. Fortunately, he spied Rob and Dave at the bleachers behind the baseball field, where they compared classes. Rob had his schedule wadded up in his pocket, and it was impossible to read. He seemed to have no clue about where he was supposed to go and cared even less. Dave had his on a clipboard, and was making notes. Neither of them had any of the same classes Marty did, so he left them and went to find his locker.

In the crowded hallways of the teenage stockyard, Marty felt terribly out of place. Being one of the smallest kids, he stuck out like the runt of the herd. He saw a couple of teammates wearing their football jerseys, and wished he’d thought of that tactic – as a way of indicating he actually belonged in high school. His ears burned from everyone staring at him, and one of the seniors laughed and informed him the middle school was on the other side of town. Marty found his locker, but it wouldn’t close all the way, so he carried his beat-up briefcase to his first class. It wasn’t all trim and pretty like the backpacks he saw that were surely bought at the mall, but it suited him just fine. It kept his drawing pens and paper neat, and ever-ready. In the back of the classroom he saw Mike and Terry from his team, and sat in the same corner. The math teacher was a friendly, very hip black man who gave out high fives and introduced himself as “Archie – don’t call me Mr. Williams or I’ll hit you upside the head with a slide rule.” Mike was half black himself, at a time when there were very few ethnic students – much less teachers – in the community. He had a copper brown Afro and green eyes that followed every move Archie made. Terry was a husky Midwestern country boy with red hair, freckles, and a shy grin.

The bell rang, but their instructor seemed to be in no hurry to actually teach the class; instead filtering through the classroom to tell jokes and greet the kids he knew. When he got to their corner, he exclaimed, “Man oh man, what do we have here? A brother, a hippie, and a redneck all sitting together! Maybe there’s hope for the world, after all.” Mike informed Marty about Archie’s background when he was out of earshot. He had been a member of the famous 1936 Olympic track & field team with Jesse Owens, and won a gold medal in the 400 meters. He was one of the black athletes who rubbed Hitler’s snotty Aryan nose in the dirt, but was remarkably humble and low-key about it. When someone asked him about those days, he’d wave it off and say, “The Germans were very nice people. Over there, I didn’t have to sit in the back of the bus.”

He was a member of the famous “Tuskegee Airmen” during the war, serving as a weather officer. He eventually rose to the rank of colonel in the Air Force, just like Marty’s step-grandfather. He never talked much about his past, because his love of the present moment and meeting people were the driving forces in his life. Having Archie as his first period teacher really helped to ease Marty’s transition into adolescence, and to being accepted in the school. He truly respected all ‘his kids’ and it was inspiring to be held in such high esteem by one who had accomplished so much under adverse circumstances. Besides, he was the first famous person Marty had ever met!

His other classes and teachers were interesting, but the real action took place in between periods. The campus was small, and the wide variety of clothing, body development, and personalities was overstimulating to Marty’s developing cartoon sensibilities. He was excited to learn there was a school newspaper without any cartoons in it! He decided he’d have to remedy that situation, once he learned what high school kids thought was funny. All the while, he kept busy just assimilating the jargon, hierarchy, and unwritten rules of behavior in high school. There was a fascinating variety of anthropological rituals all over the campus. In the front of the high school, the so-called “greasers” ruled the parking lot, loitering around their shiny hot rods and screeching their tires. (That’s where Julie hung out, though Marty didn’t see her much.) The jocks stayed near the gym (of course) …probably so their smell would be harder to notice. The popular kids strutted and fretted in the food service area, known as “the canteen.” Marty hung out in a secluded corner of the campus, right next to the baseball field, with the only friends he had. They were disdainfully referred to as the “bleacher creatures” by the more privileged students, who looked down their noses at the poor, the misfits, and the stoners, and considered them to be the most untouchable level of the high school caste system.

What amazed Marty about the bleachers tribe was how everyone was innately accepted. It didn’t matter if you were young or old, rich or poor, beautiful or ugly; everybody was bound together by a common disdain for authority, and especially for the other students higher up in the pecking order. Most of the kids smoked cigarettes, and a few of them openly smoked marijuana – albeit off-campus where they were less likely to be caught. Somebody usually had a radio blasting, and there was a unique dialect to learn if you wanted to be one of the crowd. As he’d already experienced, some kids would try to “bum” a smoke off you, and if you wouldn’t give them one, you were “tight.” A party that was particularly enjoyable was described as “radical.” Cops were referred to as “narcs,” whether or not drugs were involved in the encounter. Pretty girls were known as “babes,” and popular guys were “dudes.” The common greeting of “What’s up?” was shortened to “Sup?” The dominant topics of conversation were sex, drugs, and rock & roll – preferably a combination of all three. Mostly, the talk centered on who was having the next beer party (known as a “kegger”), and what were the prospects for scoring some weed. Although the students were literally at school, it seemed to be the furthest thing from their minds. They were interested in a “higher” education.

A typical overheard conversation might go something like this:

“Sup, dude, can I bum a smoke from ya?”

“No way man, this is my last one, no lie.”

“Aw c’mon, dude, don’t be tight.”

“I heard Joe’s having a radical kegger this weekend.”

“That’s totally awesome, for sure.”

Somehow this was not only comprehensible, but informed everyone in the tribe telepathically, the way honeybees know where the flowers are. Parties were by far the most common topic of conversation: who was thinking of having one, where the next one might be, and how radical or lame the last one was. The bleacher creatures were not academic overachievers, but they had a Ph.D. in partying! Marty met a tough, but friendly, kid from Mexico on the first day, who barely spoke any English, but knew much of the party jargon already. His name was Jorge, but he went by “George,” because that’s how all the gringos pronounced it. He was Marty’s age, but already had a thick mustache!

Suddenly, a loud voice yelled “Baldy!” and set the bleachers in rapid motion. Cigarettes were hastily snuffed out, plastic bags were stuffed in backpacks, and replaced by textbooks. A wiry man with a large, balding head stepped briskly around the corner, sporting an exaggerated comb-over, an oversized down vest, and a ratty Burt Reynolds mustache. The smoke was still thick when he started his speech about designated smoking areas, and the dire repercussions of being caught with drugs of any kind on campus. He concluded by warning he was “Mr. Ball, always on the ball,” and everybody laughed, which made him really mad because it wasn’t supposed to be a joke. Some of the bolder creatures started snickering, and coughing “Baldy!” into their sleeves, until Mr. Ball grew redder and redder, and left in a huff. Rob, Dave, and Marty grinned at each other wryly, astonished at how a group of teenagers could drive away an authority figure so easily.

Marty’s freshman football team lost its first game by a very lopsided score, but he didn’t suit up due to a lingering leg injury from the V.W. accident. The other team had its way with Drake’s smaller players, and scored touchdown after touchdown. Rob, who played safety, was running all over the field like a madman, and yelling at the defense to “do something!!” He finally took off his helmet and slammed it to the ground, earning an ejection from the officials. The players sat in sullen silence on the sidelines, wondering how such a debacle could happen, after all the practices and drills they had performed during the summer. Coach paced up and down the sidelines, tossing his clipboard aside in disgust, and hiding his mouth behind his hand, as if that would somehow conceal his profanity. The cheerleaders performed their routines listlessly until they realized they were irrelevant. They sat down dejectedly on the grass with their pom-poms, and chewed on their nails. Marty felt sorry for them, and yearned to provide them comfort in their distress.

After the embarrassment of that first game, Marty spent lots of time in the weight room after school, strengthening his weak knees and quads as well as he possibly could, because the homecoming game was fast approaching. Normally for high school football, the focus was on the varsity team, but the rookie freshman squad would be the “opening act,” and would have its pomp and ceremony as well. Marty yearned to be identified with the football team… even if they hadn’t scored a touchdown in their first game. He was confident he could improve on that, if he could just heal his leg soon. The guys on the other teams were bigger, but they looked awfully slow. Besides, there were some cute cheerleaders he wanted to impress!