And so, another day as the “new kid” at school went by quickly, with all the novel sights and faces, and then it was time to go home. Marty noticed a lot of kids liked to hang around school after it let out. He couldn’t wait to leave the place and get back to his new, park-like property. William’s house was nearby, because his father was a minister at the local church. He invited Marty to come over, but he had promised his mom he would walk Susie home – over two miles in the opposite direction. Anyway, he wasn’t too keen on visiting a church, so he waved, “Another time,” and followed a group of kids wandering down the path that led through tall green grass away from the road.

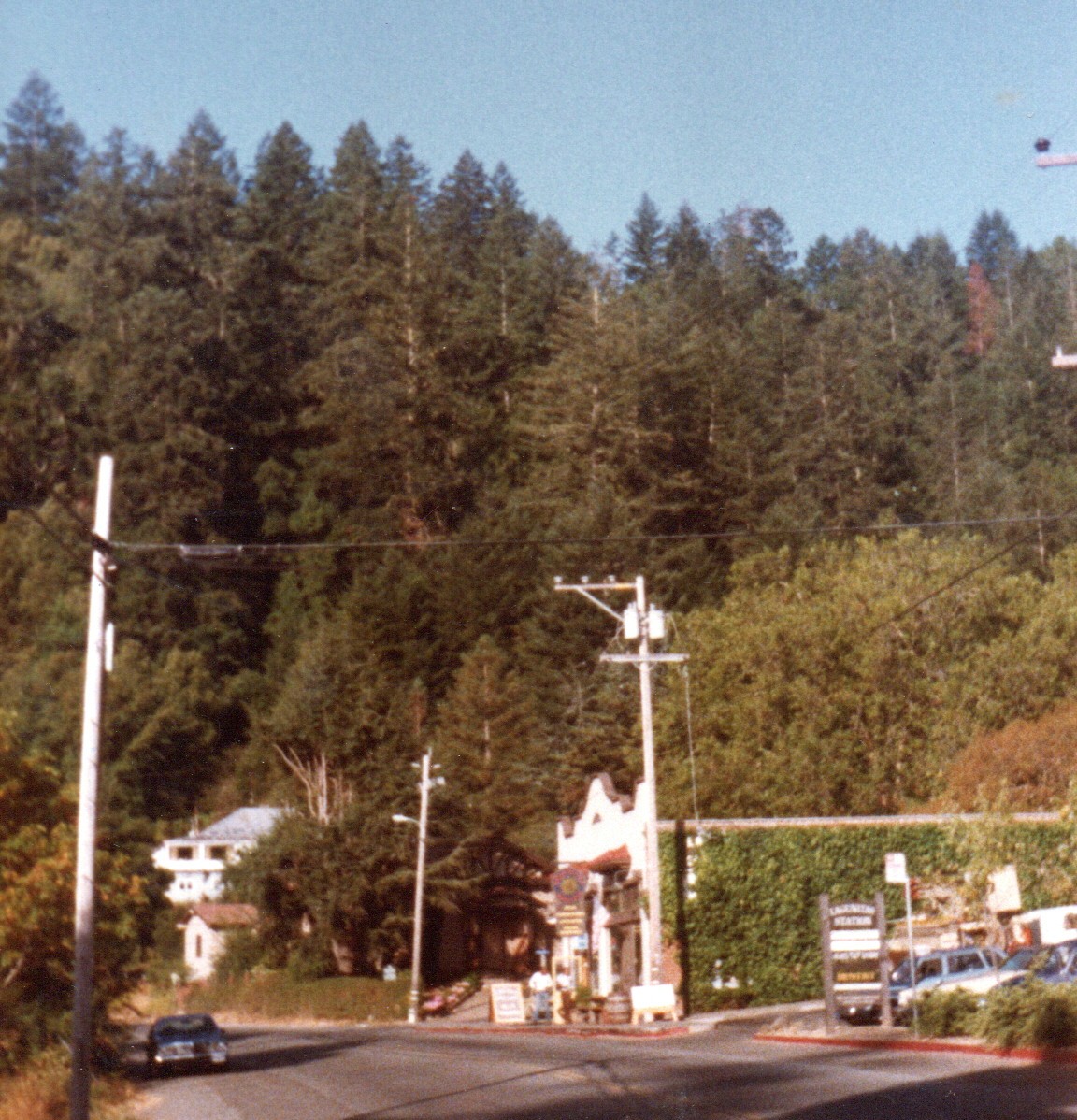

They ambled past lovely hillsides dotted with live oak, bay laurel, and Douglas firs. The scenery was even more entrancing than usual, because Alicia, one of the cute girls in his class, was one of the nine kids laughing and chatting on the trail ahead of them. As usual, Marty and Susie followed along behind the neighborhood gang, hoping to fit in. When the locals reached Forest Knolls, they dispersed and left the new kids to find their own way home. Marty was disappointed he didn’t think to ask Alicia for directions, but he figured they could just follow Papermill creek, which ran parallel to the highway and flowed right past his bedroom farther downstream. The newcomers passed landmarks like the Post Office and Speck McAuliffe’s bar, and continued down the old railroad bed to the Lagunitas Store. The antique building had the decomposing character of a relic from a bygone era, and he suggested to Susie that they stop check it out, even though they didn’t have but a handful of change between them.

The Lagunitas Store was as old as the hills, and twice as funky. Built in a pseudo-pueblo style, it featured uneven brick walls and a stucco façade with the quaintness of an early Hollywood imitation of a Spanish mission. A faded turn-of-the-century advertisement for milk was painted on one side. The front entrance sported a concrete porch, two wine barrels that had seen better days, and a couple of worn benches just a few feet off the road. The window and door trim had been painted brown a very long time ago, and were now peeling badly. This is nothing like the retail stores back in mall-ville, Marty mused dryly. Inside, the smells were ancient and layered, as if composed of every product and person that had ever been there. To the left was a stained redwood burl countertop supporting a huge, antique brass cash register – the kind where the amounts pop up on little tabs. An enameled metal case displayed all the charm of an iron lung against one wall, featuring a few sad cold cuts and withered fruit under a blinking fluorescent light. A sleepy beatnik behind the counter glanced up from his newspaper and stared at them, puzzled, because he knew all the locals and hadn’t seen these two before. On weekends there were plenty of strangers stopping off to grab some beer or snacks on their way towards the beaches in Pt. Reyes, but out-of-town youngsters rarely appeared on weekdays.

Marty and Susie acted as though they had been shopping there all their lives, and explored the dusty shelves exhibiting the usual assortment of unhealthy snacks, paper towels, and sundry items. A few fat flies circled in a listless pattern between the sunbeams from an old window that had hand-blown glass like the ones at their house. The ceiling was about 12 feet high, and hadn’t been cleaned since the place opened 70 years ago. Some wilted contents of the produce stand appeared to be more suitable for a compost bin than a salad. The ersatz shoppers wandered to the back of the cavernous building where the beer was kept in refrigerated cases that buzzed like instruments in a mad scientist’s lab. The cold cases with rows of bottles and six-packs were the most modern fixtures in the store. Marty grabbed a Yoo-Hoo, and Susie chose a 7-Up because she couldn’t decide between Coke or Pepsi. Casually, they sauntered back to the cashier as if they were the most important customers of the afternoon. Perhaps they were! The long-haired freak behind the counter announced the meager total, impatient to get back to his paper. His long, dirty blonde hair was streaked with gray, as he gazed without focus in their general direction. Red-rimmed eyes behind a pair of magenta sunglasses with square lenses hinted at a significant loss of brain cells. Marty got the impression of a cartoon hippie who had attended far too many SNACK Sunday concerts. He could sense the cashier struggling to remember what he was supposed to say in such a situation, until he finally asked, “Do you want a bag, man?”

“No thanks, these won’t last long,” Marty said brightly, to see if he would smile. Through dilated pupils and over-abused ear drums, the neurons in his brain were being sent a signal, but apparently, it found a comfortable place to lie down and never arrived at its destination. The old hippie sighed, sat tiredly on his stool, and picked up his newspaper. As they turned to leave, however, things got suddenly strange – like a bizarre scene from a foreign movie.

“It bodes an ill wind, with the buzzard at the wheel,” intoned a cryptic voice from behind the newspaper. Marty and Susie were already at the door, but froze and turned back slowly. The freak arched one eyebrow over the top of the front page. “Beware the Dead Man’s curve, and the trees at the parabola.” In the eerie silence that followed, the headlines were screaming that Saigon was being evacuated.

“What?” Marty inquired, to see if the oracle might repeat its prophecy, but the freak didn’t move or say anything more, so after a few awkward seconds he and his little blonde sister returned outside to the bright sunlight. They looked at each other and just shook their heads. Sometimes it was impossible to figure out grown-ups.

Together they shared their modest fare out on the benches; not in any hurry to get home. Susie always looked up to Marty for guidance and protection, especially in the absence of a father, and after all the changes in her young life. He knew this, but was too shy to express anything like emotions, so he simply consoled her with his presence. The sun was shining, their mom and older sister wouldn’t get back until later, and only Otter remained at their cabin. So they enjoyed the unexpected relaxation of everything being okay for a few minutes. Next to the store was a quaint, shingled Catholic church called St. Cecelia’s, neatly painted the color of the redwoods in its yard. In contrast, a rundown structure slouched across the street, with a vague resemblance to a restaurant, and a battered plywood sign announcing it was “The Old Viking.” There were boxes stacked in the windows, and Marty guessed it hadn’t been open in years. He fantasized that it was a secret speakeasy, or perhaps an opium den. The window eyes of the saints and the sinners stared defiantly across the road at each other, as they had for decades.

After finishing their treats, they walked a bit farther, and came upon a long, tight corner of the road with a battered guard rail. It dawned on him that this must be the “Dead Man’s curve,” and sure enough, a couple of thick, scarred trees bore the evidence of being hit by cars. The walking path went behind the guard rails, where a dark, spooky house was hidden next to the creek. A mossy old fence in an odd place caught his eye, and he looked through an open spot to see an ancient, decrepit wooden bridge that was rotting and falling into the creek. This could be a relic of the old railroad! Like any adventurous teenage boy, he was compelled to walk across it immediately. He slipped through the crack in the fence and stayed on the main beams, where he could see the creek and water pipe a few feet below in the gaps where decaying boards had rotted away. It only took a few seconds, and he was on the other side.

Susie didn’t want to walk across that moss-eaten death trap, so Marty had to go back and get her. He ignored a sudden vision of a board breaking and his little sister plunging to her death, and having to explain to his mom why they crossed a rotten old bridge. Leading her by the hand, they stepped tentatively on the main beam. Susie gawked at the gaping holes, and could see the creek flowing beneath them. She began to sway, and stepped on the thin slats, breaking her foot through and grabbing on to her big brother for support. “Look at me,” Marty commanded, and her eyes grabbed his like a life preserver, and they walked easily to the other side. They were 15 yards past it before she’d let go of his jacket.

A long, flat dirt road led away from the bridge, apparently a continuation of the railroad bed next to their house, so they followed it. Thick stands of alders and bay laurels covered the uphill bank, and down on the creek side they mixed with redwoods and ferns. The old road hadn’t seen any car traffic in a while, and was covered with a thick carpet of last year’s leaves. With the green boughs arching overhead, it was like walking through a beautiful green tunnel. They saw a few rundown cabins clinging to the banks across the creek. These, too, were in a state of unenthusiastic upkeep, which seemed to be the standard for the homeowner’s association in this neck of the woods. Soon they met up with the paved road again, which was called Sir Francis Drake Boulevard, and ran from San Quentin on the east shore of Marin, all the way to the lighthouse at Pt. Reyes on the west coast.

Here, in the narrowest part of the deep canyon, it was barely wide enough for two cars. The roadbed was made of concrete panels that still had the original imprint: “Ghilotti Bros. 1925.” The segments were glued together with seams of ugly black tar, which accounted for the whump-whump noise of cars passing through. Susie pointed out a white horse in a corral across the road, where the narrow concrete bridge marked the entrance to their “driveway.” Marty turned left to follow the creek downstream to their house on the opposite bank. They found another small cabin, next to a much better bridge that led across the creek to a larger house, where he could see one of the Great Danes lying in the sun.

A tall woman in a velvet maroon bathrobe came out of the cabin as the new kids reached the driveway. “This must be our neighbor,” Marty whispered and nudged Susie, who was still watching the dogs fearfully. The lady walked kind of funny, and seeing them for the first time, she stopped and gathered her fuzzy bathrobe tighter, giving the impression she didn’t have anything on underneath. “Hi, we just moved in next door,” Marty explained quickly, pointing downstream. “Can we cross the creek here?”

The woman adjusted her hair and shuffled over to where they stood. She was very tall, and smelled like alcohol. Susie instinctively hid behind her brother, with one eye on the approaching black beasts. The dogs had noticed the intruders, and came across the bridge warily, unsure if they should be barking, so they woofed just in case. Susie moved back quickly so they would eat her brother first. “I’m Paula,” the woman said in a deep voice, stopping right in front of them with his large, dirty slippers that used to be pink and fluffy. “Shut up, Rommel!” he yelled at the bigger one. “Gertrude, hush!” Marty realized all the sudden that this was a man who wore a woman’s bathrobe… and not much else except fake boobs. Wire-rimmed glasses perched on a nose shaped like a champagne cork, and his cleft chin stuck out like a miniature butt. His watery brown eyes were friendly, but guarded.

“I’m Marty, and this is Susie behind me – er, over there.” He turned to see her hiding behind an odd little car that looked like an insect. “We moved into Ron’s old place,” he turned back to say, using Camille’s description. Pablo relaxed and nodded, and then appeared lost in what was left of his thoughts. Or maybe he had recently purchased something from the freak at the store.

“Well, nice to meet you, I’ve got something to do inside.” It was said as a dismissal; not an invitation. They watched their odd neighbor retreat into his (her?) cabin, and were left to the mercy of the beasts. By that time, the dogs had decided the kids were too big to eat and too small to be of any danger, and they wagged their long tails in great sweeping swaths. Their gaping maws drooled happily for the distraction of romping alongside a thin boy and a nervous little blond girl as they crossed the bridge. Marty looked over the railing into the pools behind the dam, and could see a small canoe tied up. The whole scene impressed him with the bucolic charm of a summer camp cabin. A flagpole flew the Stars and Stripes, the California Republic, and a peace sign. On the other side, the parking spots were empty but nestled cozily in between some really big trees. The house was raised up so that the bottom story was more like a walled storage area. The whole upper story had a wraparound porch. Big, wide stairs led up to the top, where a driftwood sign hung, carved with the name “Rivendell.”

They followed a path around the house and back up on the railroad bed, passing a small, empty rabbit hutch. Rommel kept pace, at a height to look the boy in the eye, and Gertrude was big enough for the little blond girl to ride on her back, which was a bizarre image – even for a budding cartoonist. Nobody seemed to be home, so they continued down the long straight road to their gate, where the big black dogs finally turned back. They had an excellent sense of boundaries – unlike the human inhabitants of the house they would meet later.