Aquarium Beautiful wasn’t just a pet store – it was a broken-down traveling circus that was going nowhere fast. Located in downtown San Rafael, in one half of a grungy old building between D and E streets, it served as a dilapidated suspension bridge between the human and animal worlds. The eclectic establishment was run by another dysfunctional family headed by Pat, the chain-smoking owner, who dressed like a lesbian and ran her ship so tight it could fit in a bottle. Her loudmouth son, Bob, was addicted to many vices, thought he was God’s gift to women, and could sell shoes to a snake. The youngest daughter, Patty, had a remarkable talent for avoiding work, and was rarely seen except when she tried to wheedle some money from her tightfisted mom.

Pat gave Marty and Susie a doubtful interview the first day Marge brought them after school. A ubiquitous stubby cigarette dangled from one corner of her permanently downturned mouth. Her black hair was short-cropped and slicked back with a widow’s peak above a furrowed brow. The shirt she wore looked like a relic from a 50’s bowling team, and was decorated with stains of the type that could only be acquired from spending 12 hours a day in a pet store. Marty tried to avoid gawking at her tight-fitting velour house pants, or the filthy sneakers that appeared as if they might have escaped from one of the cages. He looked her right in the eye, or as well as he could through her thick, scratched glasses. Knowing that his dear mother had promised him and his sister as slaves, Marty wanted to make a good impression, and stood as straight and strong as he could at 89 lbs. and 4 feet 11 ½ inches tall. Pat squinted at them, unconvinced, wondering if either of them could perform enough meaningful work around the store to compensate for the hour that their mom would be away to pick them up from school.

“Can I feed the rabbits?” Susie asked too quickly and innocently.

“Hmm…” Pat grimaced speculatively, as if she were assessing the naïve child’s ability to avoid killing anything. She had a crafty poker face, and gave nothing away. Rapt with fascination, Marty watched the long ashes on her cigarette, wondering when they would fall off.

“I can feed the fish,” he assured her in a manly tone of competence. “We have one at home.” (It was a goldfish, and it had died of neglect soon after the divorce, but it was buried in the backyard, so technically it was still at home.)

Pat frowned as if the day-old pizza she ate for lunch didn’t agree with her. She shifted her weight and folded her arms, and still the ash did not fall off her cigarette. It was driving Marty crazy, and he had to resist the urge to reach out and flick it. “I don’t need anyone to feed anything,” she finally answered in her raspy, masculine voice. “I need people who can deal with what comes out the other end.”

Marge, always clever with improvisational skills from her college theater days, produced a broom from the corner and handed it to Susie. “Here you go, sweetie. Why don’t you sweep out the animal room?”

“Are the rabbits in there?” Susie asked hopefully.

“Yes, but you can’t hold them!” Pat croaked sternly as Susie skipped happily towards the back of the store. She was pissed because her bluff had been called. This finally made the ash fall off, and Marty sighed with relief.

“You,” she poked a stubby finger in his sternum, “Bucket Monkey. Top off all the fish tanks. That’s real work.” Then she shifted her cigarette butt to the other corner of her mouth and almost winked, as a dubious hint she wasn’t as mean as she made out to be.

Marge showed her son the proper technique to get the water the right temperature, neutralize the chlorine, and how to fill the buckets only halfway so he could lift and pour them. The aquariums were the old stainless steel framed type with ancient, bent hoods. There were 52 of them ranging from 10 to 100 gallons, bubbling in every available space of the dark and smelly fish room. The algae-covered tanks cast an eerie glow that resembled an evil scientist’s laboratory. The fish room was kept dark to feature the lighted tanks full of plants and colorful fish, so it was hard to see where exactly to pour the buckets. Marty was determined not to spill a drop, but the buckets had other ideas, sloshing violently and banging on his legs. The first time, only a little of the water actually went inside the tank (the rest went behind it, where it seemed to disappear into something disgustingly absorbent). Another time the new Bucket Monkey got an electric shock from touching two tanks at once, and he dropped a whole bucket. Pat was busy out front, arguing with the delivery guy about a load of merchandise, so she never got to see Marty’s rapid mopping skills. The uneven floor kind of squished when he stepped on it, as though it had suffered a lot of spills over the years, and it smelled bad. He wished he could be like Mickey Mouse in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, and make the mop fill all the tanks for him.

By the time all the physical labor was over, his mom and Pat were helping customers during the evening rush. Marty tried to stay out of the way, wiping the dust off shelves until he found Susie still in the animal room. With a brush she had found somewhere, she was lecturing all the rabbits (who now had names) in the finer aspects of personal grooming. He did some exploring and discovered several back rooms where customers weren’t supposed to go. The ancient pet store was a dusty warren of decades-old boxes, steep stairways, grimy corners, and piles of funky equipment – the sort you might find at a flea market. Next to the animal room, rows of cages full of nervous hamsters, rats, and mice were lined up where they could see the terrariums full of reptiles that wanted to eat them. A door in the back hall led to stairs that descended into a damp, dungeon-like parking garage, past a creepy storage area that was more like a crypt. Marty imagined himself a famous archaeologist exploring a jungle tomb, and watched for booby traps. The bathrooms in the hall were shared by all the tenants of the building, which included a cleaners and a delicatessen. A large vat full of brine shrimp belched and gurgled its low-tide smell throughout the hall, so the deli kept its back door closed. Marty held his nose and decided he wasn’t going to eat at that deli.

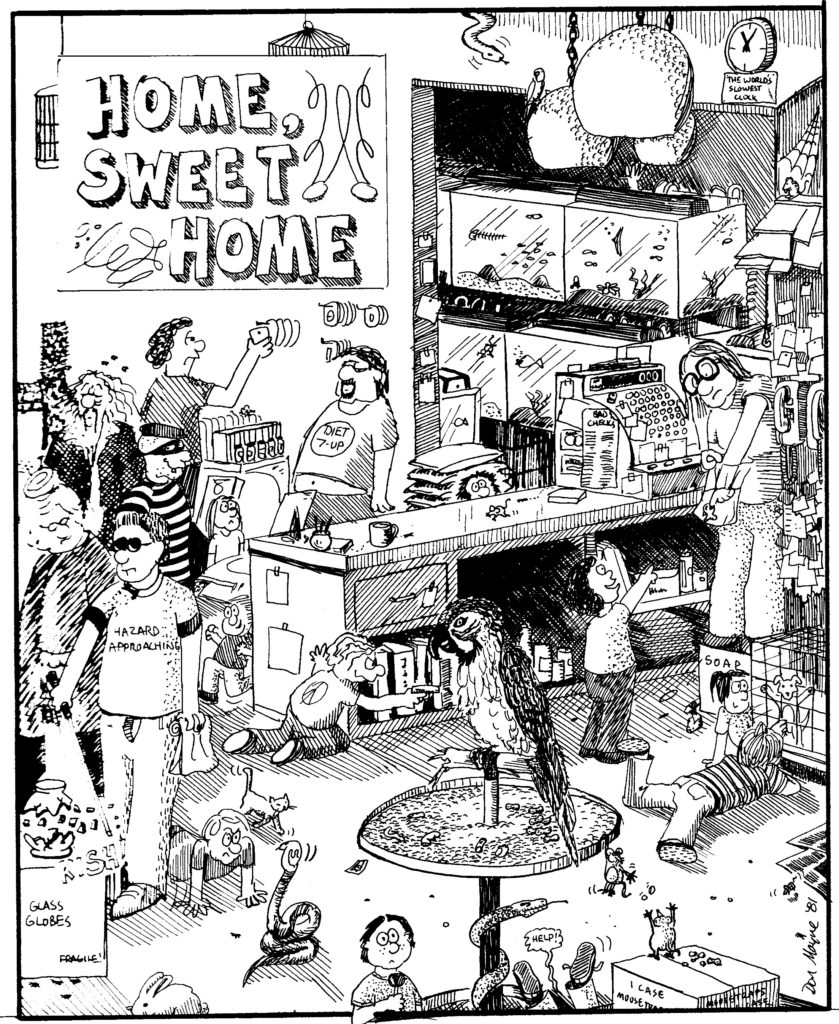

Back inside, he observed that the main part of the pet store was dominated by a large, scarred counter with a battered cash register, stuffed with thousands of papers, towels, chemicals, equipment, and old clothes in every drawer or crack. Returns and broken merchandise were jumbled together with paper and plastic bags, stacked behind the counter, or wedged next to the cash register. The walls and every flat surface were covered with small notes, business cards, and receipts taped to the wall; nearly obliterating the business license and a sign that stated, “No refunds on dead animals.” And watching over this entire chaotic menagerie with a baleful eye was Captain Hook, the store parrot.

Captain Hook was not an ordinary parrot. He was actually an irascible old pirate whose considerable bad karma caused him to reincarnate as a blue and gold Macaw, and he was really ticked off about it! Adding to the buccaneer vibe was the fact that he had only one leg. That was the result of a lost argument with a monkey, but he could still move around virtually anywhere by using his powerful beak as either a crutch or a lever. His perch was on a round platform in the middle of the store, with no cage or chains, and if his wings weren’t clipped he could have flown out the door. Knowing that flight was possible only in his dreams made him bitter and vindictive. He could see right into the soul of a person with his beady little eyes, and he either liked you or he didn’t… and he remembered forever. If he didn’t like you, his normal ruse was to lunge and feign a bite, and your reaction would tell him how much he was going to mess with you for the rest of your life. Marty got the impression he was accepted right away, but the old rapscallion faked a bite anyway just to gauge his courage. His beak was massive and unusually strong, given its necessary use as a means of locomotion. Marty could tell his range of motion was limited, but stayed just out of reach anyway. He examined the aged and battered Ara ararauna specimen thoroughly from all angles, and got a true reading on its personality. Marty decided he liked the old buzzard, too, and so began a lasting but wary friendship.

“Polly wanna finger?” He began teaching him their signature phrase. The bird pierced him with its black dagger eye as if the young human had uttered something very profound that must be shared with the world.

Captain Hook had a large vocabulary, but rarely used it when the store was open. He knew the meaning and proper context of dozens of words, and called people by name. When he got really bored or irritated, he would let loose with an embarrassing variety of expletives in a loud, screechy voice, and Bob would have to put him in the back hall, where it sounded like a muffled argument in a waterfront bar. Of all humans, Captain Hook loved Bob the most, probably because they were kindred spirits who liked their liquor and vices straight, with no watering down. Sometimes after the store was closed, he and the parrot would get drunk like randy old sailors. Bob usually had a bottle of tequila behind the counter, and kept an extra shot glass for his buddy. Whenever he saw the bottle, Captain Hook would bob his head up and down, give a loud hoot and yell, “All hands on deck!” Bob poured a few drops of booze in the glass, and nestled it in the crushed corn cobs underneath Hook’s perch. The feathered scalawag was already clambering down with unexpected dexterity. He couldn’t stand on a flat surface with only one leg, so he laid down next to the glass in such a way that he could dip his black, stick-like tongue into the liquor. Each time he tasted it, his pupils constricted and he’d hoot again: “Woop!” He never finished what he was given – he always knocked it over after a few licks and cussed loudly, with great sincerity, because he knew he wouldn’t get any more.

He learned Marty’s name right away, but called him “Mary” just to irritate him. Whenever he and Susie came through the back door after school, he would weave his head in a figure 8 motion, and mock him with “Mary-mary-mary-mary!” Marty would point to his chest and say his name slowly, but the old macaw would just cackle and do a little one-legged dance: “Mary-mary-mary-mary!” He knew this was extremely annoying, which made it all the more enjoyable. For Marty, however, it brought back painful memories… even coming from a parrot.

Marty’s father used to move the family to a new town frequently, for his own selfish reasons, and without regard for the school year or how it affected others. Once they all had to move just so he could be closer to the golf course. By the time Marty was in the 4th grade, he had gone to 5 different schools, and had to join some grades in mid-year. When they moved to their current home, he was sporting a fashionable Donny Osmond haircut with long, bowl-shaped bangs. His new teacher misread his name and introduced him as “Mary, the new girl in class.”

Aghast, Marty told her to “shut up,” out of sheer panic at what that would do to his social status at a new school. Later, as soon as he got out of the principal’s office, he got into a fight with some 6th grade thugs who were waiting to torment him. The principal got to know him very well that week.

Mr. Hastings was a benevolent soul, but had to put on a stern demeanor in his position. He inspected Marty seriously over his black-rimmed spectacles, surveying his bruised face and torn first-day-of-school clothes, and was moved with pity. He ushered the lad kindly into the library to meet Mrs. Doolittle, who turned out to be the coolest teacher in the school. She let him read the MAD magazines and comic books she kept behind the counter, and touched up his scrapes with a little iodine.

Apparently, Mr. Hastings also called Marge, because she showed up in a tizzy at lunch, demanding that the bullies be flogged, or convicted of assault, or at least expelled from school. When Marty regaled her with the embarrassing details of how the incident started, she changed her demeanor and crinkled her eyes merrily, covering her mouth and trying not to snicker, and that made him even madder. It was really tough being the new kid at school, and having to make new friends all over again. It was harder still when his own mother thought it was funny!

To try and fit in somehow, Marty developed a new skill that would make him both unique and popular, in an offbeat sort of way. He taught himself how to draw cartoons, copying from simple examples like Peanuts and B.C. to get started. After school, he would ride his bike down to the shopping mall and browse through the 50-cent paperback books that provided him with all the material he needed. Marty collected a pretty good library of his own, and brought the paperbacks to school where Mrs. Finch in the fifth grade let him display them on a shelf by his desk and loan them out to the other students. Owing to this clever public relations strategy, Marty was eventually accepted into the school hierarchy, but still heard the name “Mary” hissing from the mouths of bottom feeders that roamed the asphalt during recess, trolling for victims.

He developed an intellectual relationship with Mrs. Doolittle, who kept him supplied with books that she thought would be interesting for a shy, imaginative child. Eagerly he devoured the many volumes she provided, and hungrily came back for more. Sometimes he would stay up late to read under his covers with a flashlight, so he could return the book the next day and get another one. Stimulated by the classic outdoorsy titles she provided, like Tom Sawyer, Tarzan, Treasure Island, The Call of the Wild, and My Side of the Mountain, Marty vowed to read every book in the library before he left after the sixth grade. He didn’t make it past the literature section in fiction, but always had several books in his pack, and more in his desk.

Marty found it hard to make friends at a new school. Why bother, he’d shrug to himself in the lonely hours, it’s just a waste of time because I’ll lose them anyway. But good books are friends for life. In his family’s most recent relocation, he’d left behind a couple of friends that he never saw again. Mark was the nerd of the class, he reminisced, but we were interested in the same things, so maybe I’m a nerd, too. Walking home from school, he thought fondly of little Kim, who was more like a friend than a girlfriend (they were too young for that complication in those days). She was pretty and bright, and loved to hear him read out loud from the books he was always reading. She found it fascinating that someone could get so excited about ideas, and laughed at all his jokes. When she learned that Marty’s family was moving away, she cried and kissed him on the cheek. They huddled silently, holding hands on the bleachers at recess, lamenting the unfairness of being controlled by the whims of adults. Marty wistfully recalled that Kim was so easy to talk to (probably due to the relative lack of guile in the mind of a 10-year old), and wondered if he would ever find another girl who liked him that way. He thought the girls at his new school were a cliquish bunch, and they just giggled when he tried to talk to them about the things he liked, such as books, nature, or science. Some of them still teased him about the “Mary” incident, and that was a sure way to end any chance at a meaningful conversation.

Marty was small for his age and already going through puberty in the sixth grade. Whatever school he attended, he was usually much older than the other kids in his class, because he had to repeat preschool when Good Ol’ Dad moved them all the way out to California in 1967 from Illinois. They wound up in a bedroom town that was within commuting distance to his job at the Kodak building next to Aquatic Park in San Francisco. That was during the peak of the sweeping cultural changes that climaxed with the Summer of Love in ’68. By the time Marty finished grade school in 1974, the hippie culture was everywhere – except in G.O.D.’s house. That stern deity was straight as a rifle barrel, and too square to understand the radical changes that challenged the hypocrisy of his lifestyle.

Moving to California in those days was viewed by the rest of the country as akin to joining a cult. As far as Marty’s relatives back east were concerned, they may as well have colonized another planet. He never got to know any of his grandparents very well, and his aunts, uncles, and cousins were distant and politely indifferent. His family was entirely on its own, wandering through the outer limits of America, like the intrepid family in Lost in Space, one of the popular TV shows of the time. He was growing up at warp speed, and nobody seemed to care. No one ever talked to him about his personal feelings, or the changes in his body, and what little he knew about puberty came from dry science textbooks and references like the encyclopedias he loved to read. By the time Marty had sex education classes in middle school, it was too late to tell him anything he didn’t already know (in a purely academic sense, of course). After sixth grade, it was time to change schools all over again.

The middle school in Terra Linda was huge, and organized more like a high school with lockers and several different classes a day. Instead of satisfying just one teacher, Marty had to learn the preferences of six very different personalities. Most of the friends he knew from Oak Hill went to another middle school, so once again it was like being the new kid. The only thing that made it bearable was there were pretty girls busting out everywhere, and they were all dressed up! Some of the bold ones even wore makeup, and sashayed in the hallways like the stars on TV. The worst part was gym class, which was full of awkward, smelly boys. Each kid had his own rusty gym locker filled with rumpled gym clothes that crawled away if you forgot to shut the door. The open concrete showers got hosed down about once a month, and some of the molds and fungus growing in the corners would have been interesting entries in the science fair. Marty brought flip flops to try and avoid contact with the living floor, which made him a target for ridicule from the jocks who called him “Jesus Boy” because of his skinny body and long hair. He had started growing it long about the time his dad was no longer around to yell at him. G.O.D. had been growing more distant and pensive in the months leading up to the divorce, which happened in the summer before his son started the seventh grade. It had gotten to the point where Marty hardly saw or spoke to him, and he felt now he could do pretty much whatever he wanted.

When Marty’s birthday rolled around in October, he finally got a sign from G.O.D. Julie had a remarkable talent of anticipating when the phone would ring, and she hurled herself off the couch, scrambling with the speed of a lizard to snatch it up before anyone else could. The phone rarely rang more than once in their house because it was usually her boyfriend. She held her hand over the mouthpiece, eyes wide with exhilaration, and as casually as she could manage, mouthed “It’s Dad,” silently so his mom, who was cooking dinner, couldn’t hear.

“Who is it?” asked Marge, with a tone of voice that betrayed she already knew, due to her prodigious maternal radar.

Mary grabbed the receiver while Julie solicitously untangled the cord for him. “Hello?” He spoke uncertainly into the mouthpiece, as if he was talking to an astronaut on the moon.

“Happy Birthday!” proclaimed the tinny Voice of G.O.D., with counterfeit, disinterested ceremony.

“Um, thanks,” was about all Marty could say. His heart was pounding as if he was in trouble, and that was weird because it was his birthday and he was supposed to be happy. There was an awkward silence on the other end, a tinkle of ice cubes, and then the Voice spoke again.

“I sent you a card with a check.” The word check was emphasized as if he was teaching vocabulary to a difficult student and it was going to be on the test. “You can use it to get anything you want.”

“Oh, thank you,” Marty was recovering his senses enough to actually have a conversation. “There are some cartoon books I wanted to study for my drawings.” This detail was a hopeful but futile reminder to his father that he actually drew cartoons, on the off chance he might actually be interested in reading them. He didn’t take the bait.

“What’s he saying?” Marge asked again, beside herself with curiosity. Susie had come in from the family room, looking scared as if she was in trouble and didn’t know about it yet.

“Well, I just called to wish you a ‘happy birthday,’ but I’ve got some work here to finish up.” There was a familiar air of dismissal to the Voice, but Marty thought he sensed a wistful tone, as if his father’s life hadn’t turned out exactly the way he wanted it to, and he was putting on the best face he knew how. That insight came to him unbidden, the way one remembers part of a dream. He was beginning to use empathy for his parents as a substitute for the affection they weren’t able to give.

“Okay, thanks again dad, have a good night,” Marty offered with a lump in his throat. The receiver went click as G.O.D. hung up.

“Don’t tell me what he said, I don’t want to know,” Marge shrugged with mock indifference, vainly trying to hide the fact she cared a great deal what he said.

“He said he sent me a card. Have you seen it?” Marty knew there wasn’t one, because he brought in the mail every day, but was trying to change the subject. It didn’t work. His face was drawn and pinched, like a street urchin who had not been successful begging a meal all day.

“That son of a bitch!” Marge stabbed her meat loaf like an effigy, and Susie looked like she was about to cry.

“I’ll go check the mail,” Marty offered quickly, and scooted out the door so nobody could see the tears welling up in his eyes. He slammed the door and ran off into the golden, rolling hills for solace.